R600 Maison et ferme du Jas de Bouffan, vers 1887 (FWN238)

Pavel Machotka

(Cliquer sur les images pour les agrandir)

In Maison et ferme du Jas de Bouffan, Cézanne once again addresses the dynamics of space and pictorial surface, the interplay of denseness and sparseness, and the three-dimensional problem of recession in space through convergence (and, in one case, splaying).

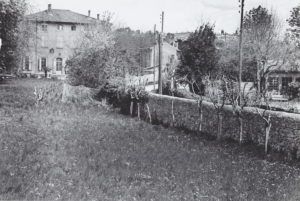

In order to comment on these matters cogently, we may compare the painting to the site photograph from 1935.

It has been proposed that Cézanne has flattened the space of the site. If we assume the photograher’s and the painter’s point of view to be the same [1], then Cézanne has indeed brought the diagonal boundary wall close to the horizontal and thereby flattened the space substantially. But the photographer’s perspective is higher; it seems clear that he (John Rewald) stood, while Cézanne sat. From Cézanne’s position, the wall would rise to closer to the horizontal. If one tilts the whole painting clockwise to bring the house to the horizontal, then the painted geometry will come close to the photographed one.

If Cézanne has not transformed perspective, what has he done, then? He has produced a painting in which he plays with the dynamics of vision, and he has in part borrowed from the motif, in part created further tension with own devices. The uncommon congestion in the center, with its balancing diagonals and complex assembly of planes, is a rendering of little pigsties; the dense center gives the painting a rhythm of compression and release. It is as if in the absence of an emphatic dividing line Cézanne has decided to help anchor and concentrate our vision by recording scrupulously the confusion that reigns in the space between the house and the farm. He has also played with our sense of space: he has taken the little farm on the right, with its walls that splay away from the viewer, and presented it to us as he saw it, frontally, with all the puzzled ambiguity it evokes. This heady rush outward arrests and puzzles our vision, but, it must be said, it does not signal a new and arbitrary conception of space.

But he has admittedly taken unusual liberty with the verticals, slanting the entire scene counterclockwise. Surely the primary reason for the tilt is the tension that it lends to the painting; to the viewer — to today’s viewer — that is justification and pleasure enough. It is radical enough to be willful, not listless as in most of the Gardanne paintings, and suggests a need on the painter’s part for a tension that the motif does not provide.

Source: Machotka, Cézanne: Landscape into Art

[1] See Erle Loran, Cézanne’s Composition, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1944.