What Copying Meant to Cézanne

The Japanese Society for Aesthetics Aesthetics No.21 (2018): 111-125

NAGAЇ Takanori

Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto

Abstract

Introduction

Did copying hold particular meaning for Paul Cézanne (1839-1906)?

Determined to become a painter, Cézanne set off for Paris in 1861. There he made drawings of the human form at the private Académie Suisse, and began to make copies of the artworks of the past at such museums as the Louvre. He took the entrance exam for the national art academy but failed. Though he gave up on that exam, he entered a succession of paintings in the government-sponsored Salons of 1866, 1867, 1868, 1869, 1870, 1872, 1878, 1879 and 1881, each rejected because they did not fit the Neoclassicist trend then controlling the Salon[i]. After the Salon was privatized in 1881, he finally had a work accepted in 1882 as the student of his friend Antoine Guillemet (1843-1918), but then lost interest in the Salon and did not enter any other works. But this did not mean that Cézanne ignored classic paintings[1]A recent exhibition reconsidered Cézanne in relationship to the Masters of the past. Judit Geskó, ed., Cézanne and the Past, exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 2012–2013.. In a process that continued into his later years, Cézanne created numerous copy drawings of works at the Musée du Luxembourg, the contemporary art museum of the period, and of the works of the past assembled at the Louvre and the Comparative Sculpture Museum in the Trocadéro, thus indicating that he maintained a strong interest in the great artists of his own period and of the past. Cézanne received official permission to make copies in the Louvre on November 20, 1863, and on April 19, 1864 he made a copy of Et in Arcadia Ego (fig. 1) by Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665). Records indicate that he re-registered for permission to copy February 23, 1868[2]Theodore Reff, “Copyists in the Louvre, 1850–1870,” Art Bulletin, no. 46, 1964, p. 555..

Fig.1 Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia ego(Les Bergers d’Arcadie), late 1630s, oil on canvas, 85 x 121 cm, Louvre Museum

In his later years Cézanne wrote the following encouragement to a young painter with whom he was in touch, Émile Bernard (1868-1941) :

“The Louvre is a good book to consult, but it should be only a means. The real, prodigious study to undertake is the diversity of the scene offered by nature.”

(To Émile Bernard, Aix, May 12, 1904)[3]Edited and translated by Alex Danchev, The letters of Paul Cézanne, London, Thames &Hudson, 2013, p.337.

“Le Louvre est un bon livre à consulter, mais ce ne doit être encore qu’un intermédiaire. L’étude réelle et prodigieuse à entreprendre, c’est la diversité du tableau de la nature.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, May 12 1904. John Rewald, ed., Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, Paris, Éditions Grasset, (nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée), 1978, p. 302.

And,

“The Louvre is the book from which we learn to read. However, we should not be content with holding onto the beautiful formulas of our illustrious predecessors. Let us go out to study beautiful nature, let us try to capture its spirits, let us seek to express ourselves according to our individual temperaments.”

(To Émile Bernard, Aix, 1905)[4]Alex Danchev, ibid., 2013, p.353.

“Le Louvre est le livre où nous apprenons à lire. Nous ne devons cependant pas nous contenter de retenir les belles formules de nos illustres devanciers. Sortons―en pour étudier la belle nature, tâchons d’en dégager l’esprit, cherchons à nous exprimer suivant notre tempérament personnel. Le temps et la réflexion d’ailleurs modifient peu à peu la vision, et enfin la compréhension nous vient.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, on a Friday in 1905. Rewald, ibid., pp.313-314.“So, the thesis to be expounded–whatever our temperament or strength in the presence of nature–is to give the image of what we see, forgetting everything that has appeared before us. This, I think, should allow the artist to give his whole personality, big or small.”

(To Émile Bernard, Aix, October 23, 1905)[5]Alex Danchev, ibid., 2013, p.355 .

“La thèse à développer est―quel que soit notre tempérament ou forme de puissance en présence de la nature―de donner l’image de ce que nous voyons, en oubliant tout ce qui apparut avant nous. Ce qui, je crois, doit permettre à l’artiste de donner toute sa personnalité grande ou petite.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, October 23, 1905. Rewald, ibid., pp. 314–315..

These comments not only emphasize the importance of studying at the Louvre, but also that of nature; not imitating the manner of one’s predecessors, but rather completely forgetting them as one understands nature anew through one’s own powers and reconstructs it on the picture plane. He emphasized, in other words, visual phenomenology, or in Cézanne’s own words, the “realization of the senses.”[6]See the following regarding the “realization of the senses”: Lawrence Gowing, “The Logic of Organized Sensations” in Cézanne: the Late Work, exh. cat., William Rubin, ed., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1977, London, Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1978, pp. 55–71; Takanori Nagaï, Motto shiritai Sezannu: Shogai to sakuhin, Tokyo Bijutsu, 2012, pp. 44–45.

Then we might ask, what was the organic connection between copying at the Louvre and “the realization” when confronting nature?

1. Oil Painting Copy Works

The Oil Painting section[7]John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne, A Catalogue Raisonné, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1996. An online catalogue that presents a corrected and supplemented version of the printed catalogue was made available online on November 20, 2013. This article uses the R. numbers used in the 1996 printed book edition. See http://www. cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/index. php. of the Cézanne catalogue raisonné by John Rewald (1912-1994) indicates that of Cézanne’s total 954 oil paintings, the following 22 works were copy works.

Fig.2 Paul Cézanne, After Frillié: Le Baiser de la muse, c. 1860, Oil on canvas, 82 x 66 cm, Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence

- Copy after Frillié, The Kiss of the Muse (R009, ca. 1960, 82 x 66 cm, oil on canvas) (copy after work in the Musée Granet (fig. 2))

- Copy after Dubufe, The Prisoner of Chillon (R013, ca. 1860, measurements unknown, oil on canvas, where- abouts unknown) (copy after work in the Musée Granet collection)

- Copy after Prud’hon, Two Children (R015, ca. 1860, 55 x 46 cm, oil on canvas, whereabouts unknown) (copy after a monochrome print)

- Either partial copy after a work attributed to Laurent Fauchier or after Albert Cuyp, Peaches on a Plate (R022, 1862-64, 18 x 24 cm, oil on canvas, private collec- tion) (copy after work in the Musée Granet collection)

- Copy after Lancret, Hide and Seek (R023, 1862-64, oil on canvas, 165 x 218 cm, Nakata Museum) (copy after monochrome print)

- Copy of a portrait photograph, Self-Portrait (R072, 1862-64, oil on canvas, 44 x 38 cm, private collection, Paris) (copy after monochrome photograph taken in 1861 by an unknown photographer)

- Copy after François Marius Granet, View of the Roman Coliseum (R027, 1863-65, measurements unknown, whereabouts unknown) (copy after monochrome print)

- Copy after Titian, Pietà (R143, ca. 1869, 19.8 x 29.8 cm, oil on paper, Rhode Island School of Design Museum) (source work unknown)

- Copy after Delacroix, The Barque of Dante (R172, ca. 1870, 25 x 33 cm, private collection, Cambridge) (copy after a work displayed in the Musée du Luxembourg or a monochrome print of same work)

- Copy after Rembrandt, Bathsheba (R173, ca. 1870, private collection, Aix-en-Provence) (copy after a monochrome print of Rembrandt painting)

- Copy after Camille Pissarro, Louveciennes (R184, ca. 1872, private collection) (copy after the original borrowed from Pissarro)

- Copy after Delacroix, Hamlet and Horatio (R232, 1873-74, oil on paper and canvas, 21.9 x 19.4 cm, private collection, Philadelphia) (copy after a monochrome lithograph)

- Copy after Armand Guillaumin, Banks of the Seine at Bercy (R293, 1876-78, oil on canvas, 59 x 72 cm, Kunsthalle Hamburg) (copy after Guillaumin’s original work)

- Copy after Barye, Tiger (R298, 1876-77, oil on canvas, 29 x 37 cm, private collection) (copy after monochrome lithograph)

- Copy after landscape photograph, Melting Snow, Fontainebleau (R413, 1879-80, oil on canvas, 73.6 x 100.6 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York) (copy after ca. 1880 photograph by unknown photographer)

- Copy after Renoir, Portrait of Cézanne (R446, 1881-82, oil on canvas, 57 x 47 cm, ermitage Museum) (copy after a pastel)

- Copy of a photograph of unknown date and photographer, Portrait of Victor Chocquet (R460, 1880-85, oil on canvas, 45 x 36.7 cm, Foundation Socindec)

- Copy after El Greco, Lady in Ermine (R568, 1885-86, oil on canvas, 55 x 49 cm, private collection, Switzerland) (copy after print reproduction of El Greco’s Lady in Ermine published in Charles Blanc’s École Espagnole)

- Copy after a photograph, Portrait of the Artist (R587, ca. 1885, oil on canvas, 55 x 46.3 cm, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh) (copy after monochrome photograph taken by unknown photographer ca. 1872)

- Copy after Adriaen van Ostade, Peasant Family (R589, 1885-90, oil on canvas, 46 x 38 cm private collection, The Netherlands) (copy after a monochrome etching dated 1647)

- Copy after Delacroix, Agar in the Desert (R745, 1890-94, oil on canvas, 50 x 56.5 cm, private collection) (source image unknown)

- Copy after Delacroix, Bouquet of Flowers (R894, 1902-04, oil on canvas, 77 x 64 cm, Pushkin Museum) (copy after watercolor)

We can infer two things from the above list. First, while Cézanne copied works from a wide range of artists, schools and periods – from the Neoclassicist Félix Nicolas Frillié (1821-1863), to the Rococo artist Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743), the 17th century Dutch Baroque artists Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Adriaen van Ostade (1610-1685), the Spanish Mannerist El Greco (1541-1614), the Romantic Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), and the Impressionist Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) — he particularly highly regarded such colorists as Titian (Tiziano Veccellio, ca. 1488-1576), Rembrandt and Delacroix, and of those he was most interested in Delacroix until the end of his life. Victor Chocquet (1821-1891), a collector of Cézanne’s works from his Impressionist period onwards, was a passionate collector of Delacroix, and he and Cézanne shared their adoration of Delacroix. Cézanne also created his Apotheosis of Delacroix in 1890-94[8]See the following regarding the relationship between Chocquet and Cézanne. John Rewald, “Chocquet and Cézanne,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, July- August 1969, pp. 33–96.. The first Cézanne exhibition was organized by the art dealer Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) in 1895, and Vollard exchanged a watercolor by Delacroix, Bouquet of Flowers, for a Cézanne work. Cézanne quickly made a copy of the watercolor after the exchange. Judging from the fact that Cézanne chose to copy works by colorists such as Delacroix, we can surmise that his aim was to study their color techniques.

However, there is one unusual fact. The majority of the source works for Cézanne’s copies were not the original oil paintings themselves, but rather reproduction prints or monochrome photographs. In other words, he copied a monochrome image that had none of the pigments’ colors or textures, and hence there were many instances where the form of the source image was before his eyes, but those source images were not models for either color or matière. The fact that he went ahead and copied the work in full color pigments under those constraints can be considered an opportunity for his active creativity regarding the colors that would not have been possible if freed from those constraints. While following the visual information provided by the model in terms of form and composition, his aim was not the re-creation of his subject, but rather he was able to spread the wings of his artistic sensibilities and freely create through pigments and brushwork. In the copy works he produced at the end of the 1860s — prior to his study of Impressionist aesthetics and techniques and namely his copies of Titian’s Pietà, Delacroix’s Barque of Dante, and Rembrandt’s Bathsheba — he used large brushstrokes and square brush strokes as planar elements and grouped them to create a sense of mass. If the couillardetechnique[9]To the best of my knowledge, this is the oldest mention of the couillarde technique. Gustave Coquiot, Paul Cézanne, Paris, Albin Michel Éditeur, 1919, pp. 62–63. of the 1860s is seen as a method in which a palette knife is used to juxtapose large patches of pigment on the canvas surface and thereby create a relief surface, then after he learned brushstroke separation in his Impressionist period, he began to re-create nature through accumulations of smaller brushstrokes. The three copy works mentioned above were experiments during this transitional period. Conversely, his faithful copying of the two works by the Impressionists Pissarro and Guillaumin that he borrowed and directly copied (namely Copy after Pissarro, Louveciennes, and Copy after Armand Guillaumin, The Banks of the Seine at Bercy) clearly indicate that his aim was to study Impressionism. However, in a copy of a sculpture he made some years later, Copy after Barye, Tiger, once again he returned to large, square brush strokes as planar elements, combining them, and thus creating forms.

In the end Cézanne would go on to develop autonomous, rhythmic arrays of parallel groupings of diagonal brushstrokes, what have been called “constructive strokes.”[10]cf. Theodore Reff, “Cézanne’s Constructive Stroke,” Art Quarterly 25, no. 3, (Autumn, 1962), pp. 214–227. And his copying from monochrome images that provided a freely creative space in terms of color and matière can be seen as providing a great opportunity to discover these brushstrokes liberated from reproductive quality. Further, in his 1885-90 copy of a monochrome etching, Copy after Adriaen van Ostade, Peasant Family, the source image provided absolutely none of the original painting’s complex and rich depiction of details, mutual interactions of form, divergence of lines or spatially complicated relationships. But he was able to freely express these elements through his color palette, in spite of the fact he had no information on the original work’s colors. Such instances allowed him to activiate his own imagination and artistic sensibilities.

Copying was not just related to technical issues. Cézanne’s elaborate copy of Frillié’s work (fig. 2) had a goal above and beyond learning Frillié’s techniques and views.

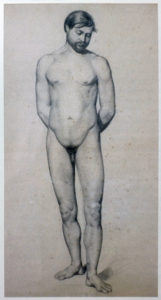

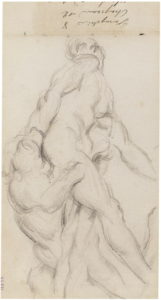

Fig.3 Paul Cézanne, Male Nude, 1862, Pencil on paper, 61 x 47cm, C0076, Granet Museum, Aix-en-Provence

Prior to moving to Paris, Cézanne first studied painting under Joseph Gibert (1806-1884), a painter in the neoclassical lineage of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). These studies took place in the drawing classroom operated by the Musée Granet in Aix. Cézanne’s drawing of the human figure (fig. 3) from this period shows a realistic depiction created through a proper grasp of form and use of shading. This indicates that for the beginner Cézanne the study of painting meant learning the techniques which would allow him to create an accurate reproduction of nature as seen by the human eye. At that time he also copied three paintings on display at the Musée Granet, creating accurate reproductions of the source works. These three works are his copy after Frillié’s Kiss of the Muse, Prisoner of Chillon and Peaches in a Plate. Of those, the Frillié work, illustrated here as fig. 2, depicts a young poet resting his arm on his desk, tired after his work at poetry composition in his writer’s garret. The Muse of poetry appears, kissing him lightly on the forehead and inspiring him. John Rewald has interpreted this selection of source imagery as a way that Cézanne sought to please his mother[11]Rewald, op. cit., 1996, Vol. I, p. 68.,[but there was another reason. Influenced by his friend from middle school, Émile Zola (1840-1902), the young Cézanne was a passionate reader of Romantic literature, including works by Alfred de Musset (1810-1857) and Victor Hugo (1802-1885). Like Zola he was absorbed in poetry composition and had first dreamed of an artistic life as a poet. Even after Zola left Aix in 1858 to move to Paris, he exchanged letters with Cézanne in which they both presented their poetry. These poems were primarily paeans to women and youth. The imaginary goddess who appears to save the poet from the suffering of the creative process could also mean his future companions who would at some point save Cézanne then suffering from the oppression of his banker father who was trying to force him into the family business[12]See Takanori Nagaï, “Sezannu no kaita joseizô” [Images of Women by Cézanne], Eureka, April 2012, No. 609, vol. 44-4, pp. 80–97.. Thus this work can be seen to reflect Cézanne’s emotional state at the time, not just a calm composed technical study.

Fig.4 Paul Cézanne, After Lancret: Le Jeu de cache-cache,1862–64, 165 x 218 cm, R023,Nakata Museum, Onomichi City, Japan

Cézanne’s concern for his father can be seen in his Copy after Lancret: Hide and Seek (fig. 4). This copy after a painter of Rococo gala scenes was meant to adorn the living room of the Jas de Bouffan, the country home that his father had bought. The house was done in an 18th century Rococo architectural style, and thus he chose a style that would suit. Previously, in 1860-1861, he had painted a Four Seasons series (fig. 5) on the curved walls of the living room.

Fig.5 Paul Cézanne, Les Quatre Saisons: Le Printemps, 1860–61, Wall painting, detached and mounted on canvas, 314 x 97 cm, Musée de la Ville de Paris, Petit Palais/ Les Quatre Saisons: L’Été, 1860–61, Wall painting, detached and mounted on canvas, 314 x 109 cm, Musée de la Ville de Paris, Petit Palais/ Les Quatre Saisons: L’Hiver, 1860–61, Wall painting, detached and mounted on canvas, 314 x 104 cm, Musée de la Ville de Paris, Petit Palai/Les Quatre Saisons: L’Automne, 1860– 61, Wall painting, detached and mounted on canvas, 314 x 104 cm

With Spring andSummer on the left, the Portrait of the Artist’s Father Louis-Auguste Cézanne, Reading “L’Événement” in the center, and Autumn and Winteron the left, these works reveal the respect and gratitude he felt for his father who had allowed him to become a painter. A Rococo style desk, chair and ceramic figurines were placed beneath these works (fig. 6).

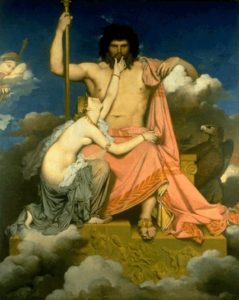

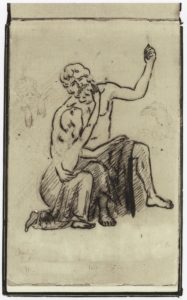

The Four Seasons is a classic theme in Western art, taken up by such painters as Poussin, and in Cézanne’s work more so than a Rococo style he demonstrates the elegant outlines, palette and smooth glossy matière of the school of Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). He included an Ingres signature in the composition, with the date 1811 written on the Winter image. The Musée Granet collection includes a work, Jupiter and Thetis (fig. 7), in Aix that is signed “Ingres” and “1811.” Thus Cézanne imitated the great neoclassical painter Ingres and sought to appeal to his father by demonstrating that he had the talents of an orthodox painter. Prior to creating his Four Seasons, Cezanne’s drawing from 1858-60 is a copy of Ingres’ Jupiter and Thetis (fig. 8). But this was a caricature, not a faithful copy, given the changes he made in the figures’ poses and actions. The subject is taken from the Iliad, and shows the scene where the goddess of water Thetis made a heartfelt plea to Zeus, the king of the gods, so that her son Achilles then at war, would be victorious. Cézanne changed the pose of the two figures, reading into Ingres’ image the latent concept of “woman sexually tempting man.” In the drawing Zeus, clasped at the neck by Thetis, looks down, uniting the two figures. Through his own personal interpretation of the Ingres painting Cézanne sought to surpass Ingres.

Fig.7 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Jupiter and Thetis, 1811, Oil on canvas, 327 x 260cm, Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence

Fig. 8 Paul Cézanne, After Ingres: Jupiter and Thetis, 1858-60, Pencil on paper, 23 x 15cm, Museum Louvre – C0050

2. Copy works in Watercolor

According to the catalogue of Cézanne’s watercolors as edited by Rewald[13]John Rewald, Paul Cézanne: The Watercolors – A Catalogue Raisonné, Boston, New York Graphic Society, 1984; French edition – Les Aquarelles de Cézanne, Catalogue Raisonné, Paris, Flammarion, 1984. The RW numbers quoted in this article are those used in these volumes., Cezanne left 645 watercolors, and of those the following six were copy works.

- Copy of a Memorial Stele (RW.64, 1878-80, 21.6 x 12.3 cm, ink, watercolor and pencil on paper, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam), (source work unknown)

- Copy after Giorgione, Pastoral Concert (RW.65, ca. 1878, watercolor and pencil on paper, 12.6 x 18.2 cm, Louvre) (Copy after either the original in the Louvre or its image published in L’Ecole vénitienne (1868) by Charles Blanc)

- Copy after Murillo, Begging Youth (RW.67, 1878-80, watercolor, gouache and pencil on paper, private collection, Paris) (Copy after original in the Louvre or illustrations in Charles Blanc’s École Espagnole (1869) or in the magazine L’Artiste)

- Copy after Delacroix, Medea (RW.145, 1880-85, watercolor and pencil on paper, 39.5 x 26.1 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich) (Copy after either the original in the Victor Chocquet collection or the illustration in the magazine L’Artiste)

- Copy after Donatello, St. George (RW.297, ca. 1890, watercolor and pencil on paper, 33.7 x 21.2 cm, Albertina, Vienna) (Copy after the plaster cast in the Comparative Sculpture Museum in the Trocadéro)

- Copy after Caravaggio, The Entombment (RW. 492, ca. 1900, watercolor and pencil on paper, 24.5 x 18 cm, private collection, Switzerland) (Copy after Pauquet’s print based on Bourdon’s drawing)

Cézanne’s watercolor copies of works reveal his interest in such colorist styles as the Venetian school, and Baroque and Romantic painters. Here too were instances where Cézanne did not copy from the full color original work but rather from monochrome prints, and thus the colors he used in his copies were entirely based on his imagination and memory of the source work. As is typically seen in his copy of a plaster cast of Donatello’s sculpture, he freely created a color palette for the work that originally had no color usage. He did not first outline an area and then apply color afterwards; rather he created a simple sense of mass and light and shadow through the juxtapositioning of contrasting color planes, while also suggesting form. Thus his methods were completely unrelated to the act of faithfully outlining a source image’s outline, rather, in his watercolor copies he experimented with translating the forms, mass, and spaces of the source work suggested by outlines and shading into the relationships between color planes.

3. Copy Drawings

Adrien Chappuis’ catalogue raisonné of Cézanne’s drawings[14]Adrien Chappuis, The Drawings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné, London, Thames and Hudson, 1973. The C numbers quoted in this article are those used in this catalogue., indicates that 1,223 of his drawings remain. Of those, there are 282 drawings that are copies of artworks, whether paintings, prints, drawings or sculpture. Further categorizing, 53 are copies of paintings, 197 are copies of sculptures, 11 are copies of drawings and 19 are copies of reproduction prints, with a further two of miscellaneous sources.

Among the paintings copied are works by Ingres, Raphael (1483-1520), Diego Velásquez (1599-1660), Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Delacroix, Paolo Veronese (1528-1588), Fra Bartolomeo (1472-1517), Bartolomé Murillo (1617-1682), Théodore Géricault (1791-1824), Francesco Bacchiacca (1494/5-1557), Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), Thomas Couture (1815- 1879), Louis Le Nain (ca. 1600/1610-1648), Horace Vernet (1789-1863), Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), François Boucher (1703-1770), Poussin, Titian, and Claude Lefèbvre (ca. 1632-1675). Overall the 53 drawing copies of paintings, with the exception of the nine after Delacroix and 22 after Rubens, reveal high regard for colorist painters. Of the 18 copies after prints, there are four after Delacroix. Of the 10 copies made after drawings, it is noteworthy that five are after Luca Signorelli (1445/1450-1523). More so than using line work to copy the non- colorist paintings of Ingres, Raphael, Gérôme and Couture, Cézanne aimed for subduing the color forms of Velásquez, Rubens, Delacroix, Veronese, Chardin, Boucher and Titian into pencil on paper and created new aesthetic value by transforming them into a new medium. In the case of replacing line with line it is possible to just transcribe as is, but in the case of copying colors into lines, the artist can take flight, spurring on artistic sensibilities and resulting in individual interpretations. When copying does not stop at the early study period stage of an artist’s career and continues until their final period, then it is not practice for study purposes, but absolutely must be considered as a creative act[15]See the following regarding the stylistic changes in Cézanne’s copy drawings. Theodore Reff, “Studies in the Drawings of Cézanne,” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, unpublished, 1958..

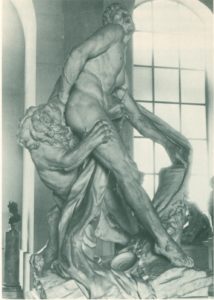

The overwhelming majority of Cézanne’s copies of artworks are images of sculptures. Of the 282 copy drawings, the 197 images of sculpture can be broken down into 50 images of ancient sculpture, 46 drawings of works by Pierre Puget (1620-1694), 15 drawings of Ecorché (the man with flayed skin) by an unknown artist, 11 drawings of works by Nicolas Coustou (1658-1733), 10 images of works by Antoine Coysevox (1640-1720), nine images of works by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714-1785), eight works by Michelangelo (1475-1564), five works by Benedetto da Maiano (1442-1497), four works by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), four works by Germain Pilon (ca. 1535/7-1590), plus an additional 35 works. As in the case of his copies of paintings, these copies of sculptures were produced throughout his life, from his early period through his final years. Even if the source work’s materials differ, whether marble, bronze or plaster, the majority of Cézanne’s copies did not involve the tracing of the outline of the source work with a limited number of lines. Rather through numerous interrupted parallel repeated lines, and their relationship with the white of the paper itself, he expressed not only the forms of the subject themselves, but also its depth, texture, light and shadows, sense of mass and sense of movement. In the limited media of white paper and black pencil Cézanne was able to condense and convey complex emotive information gained in the process of looking at his sculptural subject. Thus it was not direct translation but rather meaning interpretation. The Baroque artists Puget and Coustou, the Baroque style sculptor of Ecorché (the man with flayed skin), the classicist Coysevox, Rococoist Pigalle, Michelangelo and Maiano of the Renaissance, the neoclassicist Houdon and Mannerist Pilon indicate that Cézanne selected a variety of styles. Most of these source works have complex bone structures, dynamic musculature, whether twisted, warped, bent or clenched, and often decorative hair arrangements. Cézanne was particularly interested in Puget, who was born in Marseilles and dubbed the “Michelangelo of Provence” (figs. 9 and 10), as well as in Michelangelo himself[16]“Michel-Ange est un constructeur, et Raphaël un artiste qui, si grand qu’il soit, est toujours bridé par le modèle. Quand il veut devenir “réfléchisseur,” il tombe au-dessous de son grand rival.” Letter to Charles Camoin, Aix, December 9, 1904. John Rewald, Correspondence, p. 307.. From their complex sculptures characterized by musculature protrusion, light and dark, movement, and a sense of mass, he constructed new relationships in lines on paper while reading and interpreting their internal interrelationships, and thus these sculptures were favorable material for creative research.

Fig.9 Paul Cézanne, After Puget, Milo of Crotona, 1882-85, Pencil on paper, 19.4 x 11.8cm, Private collection, Paris, C0505

Fig.11 Paul Cézanne, La Maison du pendu, Auvers-sur-Oise, c. 1873,Museum Orsay, exhibited at the first impressionism exhibition in 1874 – R202,FWN81

Fig.12 Paul Cézanne, Les baigneurs au repos, c. 1876–77, Oil on canvas, 79 x 97cm, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia (formerly Merion), exhibited at the third impressionism exhibition in 1877

Cézanne’s repeated copying of sculptures was underscored by his strong interest in three dimensionality, light and shadow, sense of mass and sense of movement. In fact, even in his creation of paintings from his Impressionist period onwards Cézanne, unlike his colleagues, loathed the dismembering of the subject through light and shadow and dissolving it amidst atmosphere, turning instead to his own individual path, favoring firm forms, a sense of weight, and clearly defined depth (fig. 11).

If that is the case, then Cézanne’s continuing to copy sculpture until his final years can be considered to be a place for repeated honing, gaining ideas for his unique search in paintings. On the other hand, how are we to understand the other large group in his copies from sculpture, namely those of ancient sculpture? Cézanne’s interest in ancient sculpture was broad, ranging in Greek sculpture from the static works of the classical period through the dynamism of the Hellenistic period and Roman sculpture. His drawings of the human form were not only selected as material for his artistic creativity as with his drawings of other sculptures, they also allowed Cézanne to transpose these figures into his Bathers series without employing models. Georges Rivière (1850-1900) a critic active at the same time as Cézanne, commented on the Bathers (fig. 12) submitted to the 3rd Impressionist Exhibition in 1877 by Cézanne, noting its resemblance to ancient sculpture.

“M. Cézanne est, dans ses æuvres, un grec de la belle époque; ses toiles ont le calme, la sérénité héroïque des peintures et des terres cuites antiques, et les ignorants qui rient devant les Baigneurs, par exemple, me font l’effet de barbares critiquant le Panthéon.

(…) la peinture de M.Cézanne a le charme inexprimable de l’antiquité biblique et grecque, les mouvements des personnages sont simples et grands comme dans les sculptures antiques, les paysages ont une majesté qui s’impose, …”[17]Georges Rivière, “L’Impressionniste,” Journal d’art, April 14 1877, p. 2.

Fig.13 Paul Cézanne, After Luca Signorelli: Male Nude, 1866- 69, Pancil on paper, 24 x 17.8cm, Th. Werner, Berlin-C0183

Fig.14 Paul Cézanne, After Venus de Milo, 1872-73, Pencil on paper, 21.8 x 12.4cm, Private Collection, Paris -C0307

While it is highly likely that the male figure in the Bathers shown at fig. 12 was inspired by the copy of Signorelli’s human figure (fig. 13), I would like to also suggest another source, his copy of the Venus de Milo (fig. 14). Cézanne addressed the Venus di Milo (fig. 15) from face on, correcting the figure’s inclined pose and making it vertical, and thus emphasizing its sense of presence. Cézanne’s abbreviated depiction of her breasts erases the form’s female nature, while he has also changed her head to a downward looking pose. Thus the copy drawing is not a faithful re-creation of the image but rather a changed form product. This drawing is reminiscent of the male figure in the middle of the Bathers (fig. 12). The male figure is dignified in form, with face inclined, left foot stepping forward and solid chest, and yet, the swelling to right and left of his chest retain traces of the fleshiness drawn in the copy drawing. In the Bathers series, it has been indicated[18]Mary Louise Krumrine, Paul Cézanne Die Badenden, exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Basel, Eidolon/ Shchweizer Verlaghaus, Zürich, 1989; Mary Louise Krumrine, Paul Cézanne ‘The Bathers’, exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts, Basel/Eidolon, Distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1990. that many of the figures in the Bathers series are hermaphroditic in form, difficult to determine if they are male or female. And through this erasing of the male/female differentiation, it wouldn’t be at all strange for Cézanne, with his interest in the universal figural form, to have transposed the image of Venus into that of a bather.

Finally, we must note Cézanne’s affection for the classics. From childhood Cézanne read such ancient Roman poets as Titus Lucretius Carus (99-55 BC) and Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 BC), memorizing them in Greek and Latin and then working diligently at his own poems in their style and thus building an educational background based in the classical world[19]See the following regarding the connection between Cézanne and ancient utopias and Virgil. Paul Smith, Joachim Gasquet, Virgil and Cézanne’s landscape ‘My beloved Golden Age’, The magazine of the arts, Nr.148, 1998, pp.11-23./Nina M. Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence: The Painter in His Culture, Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press, 2003, pp. 187– 233./Joseph J.Rishel, Cauguin Cézanne Matisse Visions of Arcadia (exhibiton catalogue), Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2012.

See the following regarding Cézanne’s reading history, including classical literature. Matsushima Yasukazu, Sezannu to yomu gaka no shisôkeisei wo saguru [Cézanne and Reading: Tracing the Philosophical Formation of a Painter], Keiso Shobo, 1994..

Fig. 16 Paul Cézanne, After Poussin: Et in Arcadia ego(Les Bergers d’Arcadie), 1887, Pencil on paper, 20.9 x 12.2cm, Basel Museum – C1011

For Cézanne, born and raised in Aix-en-Provence in southern France, classical literature was the cultural background of his own Mediterranean world. His copies of classical sculpture that spanned his entire career, from youth to old age, were both a confirmation of his own roots, and a means of experimenting with his own creative leaps. The actual traces of his copying, in which he honed his emotions as he came into contact day by day with the elegant, still classical realm, undoubtedly nourished his classic spirit and was a source for ideas. In fact, Cézanne copied[20]See the following regarding Cézanne’s reference to Poussin. Theodore Reff, “Cézanne and Poussin,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 23, no. 1/2, (Jan. – June 1960), pp. 150–174; Theodore Reff, “Cézanne et Poussin,” Art de France, Vol. III, 1963, pp. 302–310; Richard Shiff, The Poussin Legend, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism A Study of the Theory, Technique. and Critical Evaluation of Modern Art, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago press, 1984, pp.175-187. Cézanne and Poussin: The Classical Vision of Landscape, exh. cat., National Galleries of Scotland, 1990; Kendall, Richard, ed., Cézanne & Poussin: A Symposium, Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 1993.

Cézanne’s copies of works by Poussin are C. 1011, C. 1012, and C. 1013.(fig. 16), the ancient Greek Utopia painted by Poussin as Et in Arcadia Ego (fig. 1), and for Cézanne whose artistic slogan was “Poussin refait entièrement sur nature,”[21]“Classique! Un mot ajourd’hui souvent employé à tort et à travers. Je veux le définir, du moins en ce cas: ‘Classique signifie ici: qui est en rapport avec la tradition’. Ainsi Cézanne disait: ‘Imaginez Poussin refait entièrement sur nature, voilà le classique que j’entends’.” Émile Bernard, “Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne et lettres inédites,” Mercure de France 69, no. 247 (October 16, 1907), p. 627. he did just that. In the 1880s apex of the classical period, he surpassed time and space and established an eternal image that maintains rules and proportions[22]The following study particularly asserts that the 1880s marked the height of the classicist trend.

Bernard Dorival, Cézanne, Paris, Édition Pierre Tisné, 1948, pp. 51–78., and he created a utopian realm modeled after classical Arcadia in his late years Bathers cycle.

Conclusion

Cézanne’s copy works meant more than simply learning how to look at objects and how to depict them. First, he took a liberal interpretative stance towards the forms in his copy subject, like the forms of nature, and used them as materials for his own distinctive creation. They were nothing other than the phenomenological subject for his “realization of the senses.”[23]Cézanne criticized Raphael because he was a slave to his models (in other words, he copied his models too faithfully) and conversely praised Michelangelo because of his constructive power (in other words, artistic creative power). That conviction can be seen in of his own copies. See note 17 above.. Second, the change from printed line to color paint pigment, from oil pigment to pencil lines on paper, from marble or bronze to pencil lines on paper, from a glossy flat paper print photograph to the rough texture of paint pigments, he sought to create new aesthetic values from these changes in media.

Third, the difference between a copy model and a natural model. The copy model has different rules than those of nature in that the original artist’s artistic sensibility forms its basis. His aim was to come into contact with and be stimulated by the artistic sensibility of the great artists of the past, to maneuver his own artistic sensibility, and allow the “creation of creation.” It was a competition with the great artists of the past. While according to Cézanne the artistic sensibility honed in that process must be completely forgotten when turned towards a subject in nature, contrary to his words, when he creates “une harmonie parallèlle à la nature”[24]cf. “L’art est une harmonie parallèle à la nature – que penser des imbéciles qui vous disent que l’artiste est toujours inférieur à la nature?” Letter to Joachim Gasquet, Tholonet, September 26, 897. Rewald, Correspondence, p. 262. through his phenomenological interpretation of nature, this vividly reborn artistic sensibility, “like the plank for the bather”[25]cf. “Undoubtedly―I am categorical-a sensation optique is produced in our visual organ that allows us to classify as highlight, half-tone,and quarter-tone the planes represented by sensation colorante. Ligth does not exist, therefore, for the painter. As long as you[we]pass inevitably from black to white, the first of these abstractions being a support for the eye as much as the brain, we cannot achieve mastery, self-possession.During this period(inevitably I repeat myself), we turn to the admirable works handed down to us through the ages, where we find and support, like the plank for the bather.” (Alex Danchev, op.cit., 2013, pp.347-8)

“Voici sans conteste possible―je suis très affirmatif―une sensation optique se produit dans notre organe visuel, qui nous fait classer par lumière, demi-ton ou quart de ton les plans représentés par des sensations colorantes. La lumière n’existe, donc pas pour le peintre. Tant que forcément vous allez du noir au blanc, la première de ces abstractions étant comme un point d’appui autant pour l’oeil que pour le cerveau, nous pataugeons, nous n’arrivons pas à avoir notre maîtrise, à nous posséder. Pendant cette période [de] temps (je me répète un peu forcément), nous allons vers les admirables oeuvres que nous ont transmises les âges, où nous trouvons un réconfort, un soutien, comme le fait la planche pour le baigneur.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, December 23, 1904. Rewald, Correspondence, p. 308., must have controlled his sensations.

Cézanne’s copies absolutely cannot be understood through the “realism” of the ancient Greeks and onwards, or the neoclassicist theory of copying. As eloquently indicated by the works he chose to copy, Cézanne considered the colorists and Romanticism as his starting point. There was a drastic shift of the meaning of copying from study to creation in Cézanne, who shared the values of originality, individuality, temperment and sensation that had permeated avant-garde artists since the Romanticism that sprang forth from the Enlightenment period. And in this sense also, Cézanne was a great prophet of the arts of the 20th century.

Figure Sources

Fig. 1: Denis Coutagne and Philip Conisbee, Cézanne en Provence, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, January 29 – May 7, 2006 and Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence, p. 93.

Figs. 2, 4, 5, 11 and 12: http://www.cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/index.php

What Copying Meant to Cézanne 123

Figs. 3, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15 and 16: Adrian Chappuis, The Drawings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné, London, Thames and Hudson, 1973.

Fig. 6: Cézanne – Paris and Provence, exh. cat., National Art Center, Tokyo, March 28 – June 11, 2012, p. 35.

Fig. 7: “Neoclassicism and the Arts of the Revolutionary Period,” vol. 19, Sekai Bijutsu Daizenshû, Shogakukan, 1993, p. 71.

Références

| ↑1 | A recent exhibition reconsidered Cézanne in relationship to the Masters of the past. Judit Geskó, ed., Cézanne and the Past, exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 2012–2013. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Theodore Reff, “Copyists in the Louvre, 1850–1870,” Art Bulletin, no. 46, 1964, p. 555. |

| ↑3 | Edited and translated by Alex Danchev, The letters of Paul Cézanne, London, Thames &Hudson, 2013, p.337. “Le Louvre est un bon livre à consulter, mais ce ne doit être encore qu’un intermédiaire. L’étude réelle et prodigieuse à entreprendre, c’est la diversité du tableau de la nature.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, May 12 1904. John Rewald, ed., Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, Paris, Éditions Grasset, (nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée), 1978, p. 302. |

| ↑4 | Alex Danchev, ibid., 2013, p.353. “Le Louvre est le livre où nous apprenons à lire. Nous ne devons cependant pas nous contenter de retenir les belles formules de nos illustres devanciers. Sortons―en pour étudier la belle nature, tâchons d’en dégager l’esprit, cherchons à nous exprimer suivant notre tempérament personnel. Le temps et la réflexion d’ailleurs modifient peu à peu la vision, et enfin la compréhension nous vient.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, on a Friday in 1905. Rewald, ibid., pp.313-314. |

| ↑5 | Alex Danchev, ibid., 2013, p.355 . “La thèse à développer est―quel que soit notre tempérament ou forme de puissance en présence de la nature―de donner l’image de ce que nous voyons, en oubliant tout ce qui apparut avant nous. Ce qui, je crois, doit permettre à l’artiste de donner toute sa personnalité grande ou petite.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, October 23, 1905. Rewald, ibid., pp. 314–315. |

| ↑6 | See the following regarding the “realization of the senses”: Lawrence Gowing, “The Logic of Organized Sensations” in Cézanne: the Late Work, exh. cat., William Rubin, ed., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1977, London, Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1978, pp. 55–71; Takanori Nagaï, Motto shiritai Sezannu: Shogai to sakuhin, Tokyo Bijutsu, 2012, pp. 44–45. |

| ↑7 | John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne, A Catalogue Raisonné, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1996. An online catalogue that presents a corrected and supplemented version of the printed catalogue was made available online on November 20, 2013. This article uses the R. numbers used in the 1996 printed book edition. See http://www. cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/index. php. |

| ↑8 | See the following regarding the relationship between Chocquet and Cézanne. John Rewald, “Chocquet and Cézanne,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, July- August 1969, pp. 33–96. |

| ↑9 | To the best of my knowledge, this is the oldest mention of the couillarde technique. Gustave Coquiot, Paul Cézanne, Paris, Albin Michel Éditeur, 1919, pp. 62–63. |

| ↑10 | cf. Theodore Reff, “Cézanne’s Constructive Stroke,” Art Quarterly 25, no. 3, (Autumn, 1962), pp. 214–227. |

| ↑11 | Rewald, op. cit., 1996, Vol. I, p. 68. |

| ↑12 | See Takanori Nagaï, “Sezannu no kaita joseizô” [Images of Women by Cézanne], Eureka, April 2012, No. 609, vol. 44-4, pp. 80–97. |

| ↑13 | John Rewald, Paul Cézanne: The Watercolors – A Catalogue Raisonné, Boston, New York Graphic Society, 1984; French edition – Les Aquarelles de Cézanne, Catalogue Raisonné, Paris, Flammarion, 1984. The RW numbers quoted in this article are those used in these volumes. |

| ↑14 | Adrien Chappuis, The Drawings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné, London, Thames and Hudson, 1973. The C numbers quoted in this article are those used in this catalogue. |

| ↑15 | See the following regarding the stylistic changes in Cézanne’s copy drawings. Theodore Reff, “Studies in the Drawings of Cézanne,” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, unpublished, 1958. |

| ↑16 | “Michel-Ange est un constructeur, et Raphaël un artiste qui, si grand qu’il soit, est toujours bridé par le modèle. Quand il veut devenir “réfléchisseur,” il tombe au-dessous de son grand rival.” Letter to Charles Camoin, Aix, December 9, 1904. John Rewald, Correspondence, p. 307. |

| ↑17 | Georges Rivière, “L’Impressionniste,” Journal d’art, April 14 1877, p. 2. |

| ↑18 | Mary Louise Krumrine, Paul Cézanne Die Badenden, exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Basel, Eidolon/ Shchweizer Verlaghaus, Zürich, 1989; Mary Louise Krumrine, Paul Cézanne ‘The Bathers’, exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts, Basel/Eidolon, Distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1990. |

| ↑19 | See the following regarding the connection between Cézanne and ancient utopias and Virgil. Paul Smith, Joachim Gasquet, Virgil and Cézanne’s landscape ‘My beloved Golden Age’, The magazine of the arts, Nr.148, 1998, pp.11-23./Nina M. Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence: The Painter in His Culture, Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press, 2003, pp. 187– 233./Joseph J.Rishel, Cauguin Cézanne Matisse Visions of Arcadia (exhibiton catalogue), Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2012. See the following regarding Cézanne’s reading history, including classical literature. Matsushima Yasukazu, Sezannu to yomu gaka no shisôkeisei wo saguru [Cézanne and Reading: Tracing the Philosophical Formation of a Painter], Keiso Shobo, 1994. |

| ↑20 | See the following regarding Cézanne’s reference to Poussin. Theodore Reff, “Cézanne and Poussin,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 23, no. 1/2, (Jan. – June 1960), pp. 150–174; Theodore Reff, “Cézanne et Poussin,” Art de France, Vol. III, 1963, pp. 302–310; Richard Shiff, The Poussin Legend, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism A Study of the Theory, Technique. and Critical Evaluation of Modern Art, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago press, 1984, pp.175-187. Cézanne and Poussin: The Classical Vision of Landscape, exh. cat., National Galleries of Scotland, 1990; Kendall, Richard, ed., Cézanne & Poussin: A Symposium, Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 1993. Cézanne’s copies of works by Poussin are C. 1011, C. 1012, and C. 1013. |

| ↑21 | “Classique! Un mot ajourd’hui souvent employé à tort et à travers. Je veux le définir, du moins en ce cas: ‘Classique signifie ici: qui est en rapport avec la tradition’. Ainsi Cézanne disait: ‘Imaginez Poussin refait entièrement sur nature, voilà le classique que j’entends’.” Émile Bernard, “Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne et lettres inédites,” Mercure de France 69, no. 247 (October 16, 1907), p. 627. |

| ↑22 | The following study particularly asserts that the 1880s marked the height of the classicist trend. Bernard Dorival, Cézanne, Paris, Édition Pierre Tisné, 1948, pp. 51–78. |

| ↑23 | Cézanne criticized Raphael because he was a slave to his models (in other words, he copied his models too faithfully) and conversely praised Michelangelo because of his constructive power (in other words, artistic creative power). That conviction can be seen in of his own copies. See note 17 above. |

| ↑24 | cf. “L’art est une harmonie parallèle à la nature – que penser des imbéciles qui vous disent que l’artiste est toujours inférieur à la nature?” Letter to Joachim Gasquet, Tholonet, September 26, 897. Rewald, Correspondence, p. 262. |

| ↑25 | cf. “Undoubtedly―I am categorical-a sensation optique is produced in our visual organ that allows us to classify as highlight, half-tone,and quarter-tone the planes represented by sensation colorante. Ligth does not exist, therefore, for the painter. As long as you[we]pass inevitably from black to white, the first of these abstractions being a support for the eye as much as the brain, we cannot achieve mastery, self-possession.During this period(inevitably I repeat myself), we turn to the admirable works handed down to us through the ages, where we find and support, like the plank for the bather.” (Alex Danchev, op.cit., 2013, pp.347-8) “Voici sans conteste possible―je suis très affirmatif―une sensation optique se produit dans notre organe visuel, qui nous fait classer par lumière, demi-ton ou quart de ton les plans représentés par des sensations colorantes. La lumière n’existe, donc pas pour le peintre. Tant que forcément vous allez du noir au blanc, la première de ces abstractions étant comme un point d’appui autant pour l’oeil que pour le cerveau, nous pataugeons, nous n’arrivons pas à avoir notre maîtrise, à nous posséder. Pendant cette période [de] temps (je me répète un peu forcément), nous allons vers les admirables oeuvres que nous ont transmises les âges, où nous trouvons un réconfort, un soutien, comme le fait la planche pour le baigneur.” Letter to Émile Bernard, Aix, December 23, 1904. Rewald, Correspondence, p. 308. |