1930–40 年代の日本におけるセザンヌの受容

Cézannisme in Japan 1922•1-1947•1

課題番号10610053

平成 10-13 年度文部科学省科学研究費補助金基盤研究(c) (2)研究成果報告書

Report on Research conducted under the Auspices of the Scientific Research Grants

For 1998-2001, Base Research(c)(2) by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology

平成14年3月

2002•3

研究者:永井隆則

京都工芸繊維大学助教授

研究者番号:60207967

Researcher: Takanori NAGAÏ

Kyoto Institute of Technology

———————————————————————————————————————

平成10 -13 年度文部科学省科学研究費補助金研究成果報告書

機関番号:14303

研究機関名:京都工芸繊維大学

研究種目名:基盤研究(c)(2)

研究期間:平成10年度-平成13年度

課題番号:10610053

研究課題名:1930-40年代の日本におけるンヌの受容

研究者番号:60207967

研究代表者名:永井隆則

研究費:800千円(平成10年度)

900千円(平成11年度)

1100千円(平成12年度)

700千円(平成13年度)

計3500千円

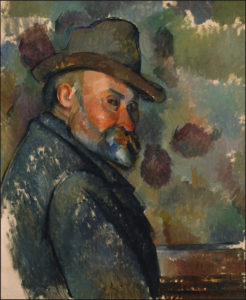

表紙挿絵:ポール・セザンヌ作《帽子をかぶった自画像》油彩•カンヴァス,61,2 X 50.1 cm 1890-1894年頃、ブリヂストン美術館蔵 © 石橋財団ブリヂストン美術館

Cover image: Paul Cézanne <Selfportrait with a hat> Oil and canvas 61.2×50.l cm c.1890-94

©Ishibashi Foundation Bridgestone Museum of Art

——————————————————————————————————————

Cézanne’s Reception in Japan During the 1930s

From “Personality (Jinkaku)’’ to “Plastique(Formality/Zokei)’’

Professor Takanori Nagaï Kyoto Institute of Technology

Introduction

Born in 1839 and deceased in 1906,the French painter Paul Cézanne was essentially introduced to Japanese audiences after about the year 1910. I have previously conducted investigations in order to trace Cézanne’s reception from around 1910 on,1but in this essay I would like to offer a hypothesis concerning the type of critical reception to Cézanne’s work that was particularly conspicuous during the 1930s. Before I develop this hypothesis, however, I would like to establish a common ground for discussion by introducing the styles of criticism that took shape during the 1910s and 20s. Since this is material that has been previously presented elsewhere and space is limited, I will confine myself to a summary of the representative critical works.

- Images of Cézanne in the 1910s and 20s

⓵ Humanist Theory

Critical approaches to Cézanne’s work may be concisely divided into two styles. One style sought less to describe the formal, perceptual characteristics that could be observed in a given piece of work and instead used them to intuit and describe the creator Cézanne’s personality and lifestyle. I will provisionally refer to this as the Humanist theory. As one example, let us take Muneyoshi Yanagi(1889-1961)’s article « Revolutionary artists”2 Inspired by the Manet and Post-Impressionismexhibition that was organized in 1910 by the English critic Roger Fry (1866-1934), Yanagi classified Vincent van Gogh (1853-90), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903),Cézanne, and Henri Matisse (l869,1954) under “post-impressionism” and discussed the revolutionary quality of these artists in the context of art history. That is, while the impressionists passively represented natural impressions and the néo-impressionists scientifically analyzed them, the “post-impressionists” were distinguished by their “active projection of themselves onto nature” (p, 9) and their expression in paintings of “the life of the self” and “personality” (p. 10). In their painting, Yanagi assert, there is “an irrepressible, earnest expression of human life” and “human life and art are unified’’(p. 23), This is the perspective from which he describes the four painters. In his observation of a Cézanne still life (an unidentifiable work), Yanagi finds a “sureness and simple honesty” and a “modest grandeur” ; indicating an »authority on personality » therein, he sees a »solid career” and “a steady and pure character » in “its immovable, powerful sort of surety” (pp. 13-14). In contrast to “Cézanne’s majestic passivity”, Van Gogh is an “intensely active personality” and a person who “directly painted the inner cry”to him, writes Yanagi, “art was already none other than life itself” (pp, 14-19). He sees Gauguin’s paintings as “works simplified in terms of color and form”, “flat, primitive” paintings with a “placid, peaceful, quiet beauty” in which resides Gauguin’s “innocent heart.” And he finds Matisse’s paintings characterized by “simple brushwork” and the realization of Matisse’s demand for “confidence” “certitude” and “consciousness” in his own life (pp- 24-26).

While touching upon the formal characteristics of the four artists’ works, Yanagi both projects biographical information upon them and, conversely, infers from them the personalities and lifestyles of the artists. Moreover, the characteristics of the four artists Yanagi extracts through his Humanist theory are esteemed as ideals of character and lifestyle, and artistic worth is replaced by moral worth.

② Personalism

The other style of criticism is the “Personalist” perspective. In order to avoid creating misunderstanding, I want to first note that the « personality » (jinkaku)of Personalism (Jinkakushugi)is not the personal characteristics that express personality or character in Yanagi’s usage. In the texts of Kitaro Nishida( 1870-1945), who developed an artistic theory on the Personalist point of view from the 1910s to the 1920$,“personality” is used interchangeably with expressions such as “the agency of action,” “volition,” “self,” and “rhythm of life”;the “personality” that is invoked in the artistic criticism of that era was used in the sense of a formative power that ruled and manifested such things as the artwork’ surface color and form from behind, as a characteristic continuum or whole.3Personalism tied artwork and artist in a cause and effect relationship and shared the Humanist theory’s standpoint that the origins of formal features may only be sought in the artist’s individuality. However, the Humanist theory confused the artist’s everyday life and quotidian character with an image inferred from their artwork. By contrast, the “personality” or Personalism was ultimately the artist’s will, agency, vital movements and flow, to the extent that they could be intuited from behind the artwork’s formal features, and was distinct from a personal image inferred from biographical information4In the artistic criticism of the 1910s and 20s there are also instances where, depending upon the critic, “personality” is used in both the Humanist and Personalist senses of the word. But I distinguish between the two and restrict the latter to the foregoing limited meaning.

As such, Yanagi’s essay on van Gogh entitled “The problem of vitality,”5which was published in the year following his « Revolutionary artists” piece, is no longer Humanist criticism. Concerning van Gogh’s “Cypress” (an unidentifiable work),he makes the following comments: “it is fundamentally impossible to understand this painting simply on the basis of its color, brushwork, configuration, perspective, shading, et cetera. At the heart of all understanding is the awareness of a unified life force that lies behind these sort of elements” (p, 70). The vitality of van Gogh that supports the painting’s material, formal composition from behind is ultimately life as a formative force that can be perceived separately in the work of art, and in this sense is based on the Personalist criticism.

Moreover, in his April 1910 essay in the journal Subaru,« Green sun”6Kotaro Takamura( 1883-1956) seeks in each artistes « Persönlichkeit”a standard for appreciating their works of art and claims that he wishes to judge an artwork’s value based on the amount of the artist’s « Das Leben »that appears in the work. This perspective was previously employed by Takamura in a Subaruessay published in January of the same year entitled “A last look at the third Ministry of Education exhibition”,5and it would become established as his form of criticism. In this piece he critiques the Ministry of Education exhibit’s sculptural works and, while noting such elements as ”brushwork”, « feeling”, « structure”, »surface” and « mouvement »,seeks the ultimate standard of the artwork’s worth in whether he himself can sense the artist’s “life” (la vie, Das Leben)behind the work, and whether that life is shallow or deep. Among the entries in the exhibit, Takamura also praises Morie Ogiwara(1879- 1910)’s Portrait of Torakichi Hojoand writes that “behind the work is visible an infinite life (la vie)”, the depth of which “comes spontaneously from the artist’s personality”(p. 28, pp.41-3).

It is the same case with Takamura’s 1915 book Impressionist Thought and Art7This work refers to the contemporary texts of Camille Mauclaire (1872-1945), Théodore Duret (1838-1927), Emile Bernard (1868-1941), and Julius Meier-Graefe (1867-1935) to provide a wide-ranging introduction to biographical facts, such elements as “color”, “brushwork”, “matière”,motif, and the state of French thought at the time. In this sense it stands out from the crowd as a book on the impressionists written by Japanese. Yet when he defined art in passages such as the following one, Takamura fundamentally shared the critical standpoint of his contemporaries Yanagi and Nishida: “Art is not style. Nor is it technique. It is free from all of this. The alignment of brushstrokes, the distinctions of hue, uplift, brightness, tone – the fates of all of these are decided by the life of the soul that influences them. In Alfred Sisley (l839-99) they die, in van Gogh they live. In Manet’s case they are shallow, in Cézanne they are deep”,(pp. 402-3) He describes Cézanne as “reserved” and “timid” and possessing “to an unusual degree such phenomena as carelessness, clumsiness and nervous hypersensitivity in his daily life » but on the other hand having “an arrogance towards common people”(pp. 393, 399). Yet in distinction to this everyday image he describes Cézanne’s vitality in the following terms : taking a still-life (identity unknown) as an example, he writes that behind its arrangement there is “a universal life of infinite weight”, “the rhythm of his [Cézanne’s] heart” and “a force of total personality that has given forth a mighty body and soul”(pp. 401-402).

Once we enter the 1920s, we find two books on the history of modem French painting that use personality as a standard to distinguish artists and works of art : Sotaro Nakai (1879- 1966)’s Introduction to Modern Art8and Juzo Ueda(1886-1973)’s Essays on the History of Modern Painting9. Nishida, whom we introduced above, noted the way in which — unlike the impressionists — the so-called post-impressionist paintings of Cézanne, van Gogh, Gauguin and Matisse vividly revealed the ”personality” of the artist. As a concrete expression of this he distinguished the ”character” of these four artists, with van Gogh as “dynamischer Organisumus”, Gauguin and Matisse as “the power of melody (Lyrismus)added to van Gogh’s dynamische Farbe”10and Cézanne as « Ordnung des Ganzen”or »absolute Gestaltung”11.For his part, Takamura used expressions such as the presence or absence of ulifenand the depth and amount of that life in order to distinguish « personality” {Zokeibiron, pp.402-3), but it is difficult to say that either man sufficiently described the actual differences in “personality.”12In the case of Nakai and Ueda, by contrast, certain tropes were added to “personality” as a standard for describing differences in artists and works of art. Throughout Nakai’s history of painting one finds descriptions in common with the Humanist style of criticism, with both the artist’s character as well as the life that defines an artwork described by turns and interchangeably. Nevertheless, concerning Gauguin’s “Two young women of Tahiti” (unidentifiable work),he notes the presence of a “quiet, forceful saturation of life” in its “form and composition.”13With reference to Cézanne’s “Bathing goddess” (the present Great Bathersin the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art), he interprets its “composition” as not following an academic style but rather being unified by “a single rhythm » and single function”, and its modulation of color not as « decomposition” but as a “synthetic” method “filled with inner life” (pp.159,209), Ueda uses the expression “artistic personality”14and while distancing himself from the « personality » of the Humanist criticism, describes in van Gogh’s brushwork “the tumult of a stormy life,’’ “a movable force, a vitality stretched tight to bursting”(pp, 669-712),in Cézanne’s “Apple and Lemon” (unidentifiable work) “a keenly vigorous life and a deep spirit” (pp. 713-753),and so on.

⓷The Environment of Personalist Criticism

As I have already shown elsewhere15, it is impossible to consider Personalist criticism apart from the contemporary climate of thought that placed absolute value on individual life and the “Vitalism”(seimeishugi)that permeated a variety of social spheres including literature and women’s liberation thought16. It was also related to the ethics that sought value in the individual self and subjectivity and the anti-materialist thought that were developed in Jiro Abe (l 883-1959)’s 1922 book Personalism.17Speaking solely with respect to artistic criticism, the system of values that prioritized an underlying spirit over painting technique and material composition demonstrates the posture of receiving Western modem art as spirit rather than technique. This was not a denial of Japanese identity or the identity of Japanese art; on the contrary, it was a viewpoint from which one could derive great security. One can see therein a skillful passive mechanism that received the Other without denying the Self. In fact, attendant upon the reception of modem Western painting was a contemporary revival of artistic discussion concerning Japan’s Nanga school of painting, and several texts were written critiquing impressionism and post-impressionism based on their resemblance to Nanga painting18.”Personalism » was a form of criticism that matured independently in the Japanese environment, and Cézanne was also received within its framework of perception.

- 1930s « Realism (Shajitsu)”and the « Plastique »reception of Cézanne

⓵The Problems with Personalist Criticism

The image of Cézannecreated by Personalist criticism had three problems. In the first place, it did not end up evaluating and sufficiently articulating the autonomous order of the formal elements in Cézanne’s painting. Secondly, as is clear from Nishida’s text, “personality » was understood as a dynamic formative agent that produced the phenomena of color and shape. However, Cézanne’s « life » was just articulated as a fixed characteristic or simply renamed as rhythm or the flow of life, and there was no concrete explanation for how these things were intertwined with the painting’s form or composition as figurative agents. In the third place, Personalism did not sufficiently discuss the connection between Cézanne and his natural subjects, and further, their relationship to his paintings, which one would expect to be another important aspect of production.19Next I would like to introduce my hypothesis that in the 1930s the foregoing type of Personalist criticism was discarded and two styles of criticism took root. One of these was “Realism,’’ the other, “Plastique(Formality/Zokei)”

②Realism

Cézanne regarded as « forming » the process whereby he materialized in his paintings the reality of his natural subjects, and the Realist reception of Cézanne focused upon the articulation of this process. Representative of this effort was the article “The Raison d’être of Realism”20published in 1935, and two articles of Cézanne criticism published in 1939, « Cézanne and nature”21and »Cézanne’s aesthetics”22. Kunitaro Suda (l891-1961) rejected both figurative paintings that repeated the post-Renaissance Naturalism while affecting Objectivism as well as the extreme subjectivism that disregarded the observation of natural subjects. He advocated “Realism” as a third way, in which nature was viewed with one’s own eyes and one’spersonal perspective was materialized as reality in the painting through “forming.” For his model, he looked to Cézanne. As an example of Cézanne’s forming, Suda notes his technique of apprehending the subject, particularly in the relationship of color gradation. In Cézanne’s words, this was ”modulation”.The first detailed account of this technique comes from Emile Bernard, who visited Cezanne in 1904 while he was still alive and working in Aix.23Suda is clearly referencing Bernard’s text, but his interpretation differs from the interpretation of the previous period’s Personalist criticism. By way of comparison, I would like to once again refer to Takamura’s book Impressionist Thought and Art (1915).As expected, Takamura references Bernard, translating modulationinto Japanese as sui’i (change/transition),and compares it to “the succession of sounds in music,” “friction,” and “flow”, noting that this is what creates the shape and roundness of objects on the painting’s surface. Yet he finds the all-important key that guides this process in the usensationcolorante’’(translated into Japanese as “color feel” by Takamura): “while it is very distinct, it always appears with a mysterious depth somewhere, ’’ he writes, and also describes it by saying that “behind it flows Cézanne’s living blood. 1922”24

By contrast, Suda interprets modulationas a “formative” process that is ultimately a succession of perceptual processes. Through modulationthe opposition between color and line is dissolved, shapes are created via the mutual contact of color surfaces and, in the process, “contortions’, “’distortion”, “deformation”, « simplification” and the “geometricization of shapes” occur. This interpretation contradicted the prevailing interpretation of the time concerning Cézanne’s famous formula, related in a 1904 letter to Bernard. The formula was as follows: “deal with nature as cylinders, spheres, and cones, all placed in perspective so that each aspect of an object or a plane goes toward a central point,25In the critical context of 1932 book Essays on Pure Painting,32he calls one of the trends of twentieth century figurative art »Realism” but in the case of those artists who followedCézanne such as Henri Rousseau (1844-1910), Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958), Georges Rouault (1871-1958) and Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955), Toyama notes that nature has become a disguise for pure painterly expression. Unlike Suda and Yasui, Toyama stressed Cézanne’s plastique(in his words,“the emphasis on color feeling and form guided by decorative significance”, « simplification”, “deformation”, and « composition through surfaces” (pp. 152-159) rather than the “reality” of Cézanne’s realism. Toyama held that in Cézanne’s case, paintings formed solely as a result of their internal, autonomous order — that is, “pure paintings” — took shape (p.100). Toyama further notes that on the basis of Cézanne’s famous formula, Cubism, or “formalism”in Toyama’s words, was born (p,100).

Similarly, and in the same period, Kotaro Takamura shifted his critical standard of value from « personality” to « ‘plastique ».In Takamura, the hierarchical relationship between the two was reversed. In his 1933 essay “Modern Sculpture”33he sums up Cézanne’s place in the history of art by saying that “as a result of the pursuit of nature in his paintings, he achieved the break up of concreteness and ultimately contributed suggestions to the theory of the Cubists and abstractionists” (p. 182). In his 1940 article « Subject matter and plastique« 34 he distinguishes plastiqueas the creation of a shape (surface pattern) from forming as the creation of a form (p. 6), As the formative elements that realize the plastique,he mentions « the disposition of space”, « quantity”, and “plan” and their »balance”, “proportion”,and “relationship of movement”, and, in the case of painting, particularly such elements as “balance of color”, “reciprocity”, “harmony”, and “brushwork”;Takamura holds that it is precisely the « ‘plastiquebeauty » these elements achieve that is the essence of plastique(formalistic) art (pp. 1-72). As a critical perspective also capable of evaluating abstract art (which had already achieved acceptance), the Formalist perspective is shown in the following terms:“As the most reliable basis for the so-called abstract art that does not deal with the form of natural objects, the pure aesthetic of these formal elements must be unambiguously present. Otherwise, it is merely a trifling caprice. Moreover, to those who do not comprehend the nature and beauty of these elements, abstract art will no doubt be absolute nonsense” (p. 25).

Furthermore, Takamura explains the trends of modem French painting in the following description that employs what is today the most familiar description of modern painting’s developmental history: »realizing the essence of plastique,(they) expelled the photographic quality of misleading paintings beyond the boundaries of art and created a succession of such extreme art movements as post-impressionism, Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Futurism, Purism, and Abstractionism that continues to the present day.”35

Conclusion

This paper presented that Toyama and Takamura offered the image of Cézanne that is widely held today, that of the originator of Cubist and abstract art, and we also introduced the circumstances under which was established the critical perspective that articulated not only Cézanne but modern painting in general as the autonomous order of the painting’s surface itself. In art criticism’s shift in style and value standard from »personality » to« plastique »,the Realist critique of Cézanneappears peculiar. However, in his 1947 “Cézanne in Japan”36and his 1950 “Cézanne, Derain, and Sotaro Yasui : the nature and position of Realism,”37Teiichi Hijikata (1904-80) joins Suda in criticizing the image of Cézanne,already established at the time, as the father of Cubism, and argues for the possibility of Cézanne’s reception from a Realist perspective. Furthermore, in his 1935 “The raison d’être of Realism”38, Suda asserts that “Ultimately, Realism’s reason for existence must be seen in the common ground between artistic reality and actual reality. From that perspective, is not Realism given the potential for unlimited development?” In fact, while formalist criticism as a system strongly determines our gaze and has made it difficult to see, when we turn from the Realist critical style to reexamine the scene of postwar production, we can confirm that the “Modem Figurativist” lineage that referenced Cézanne, among others, Suda, Umehara, Yasui, Toku Satake (1897- ), Shonosuke Mikumo (1902-1982), and Kenji Yoshioka (1906- ) in Japan, and Matisse, Picasso, and Derain in France persevered in a deep-rooted fashion. Realist criticism is worth noting for its suggestion that the Modem Figurativists constituted yet another trend in twentieth century art.

[Footnotes]

- Please refer to my article “An Aspect of Cézanne’s Reception in Japan: The Formation and

Development of the Personalist Interpretation of Cézanne in the 1920s”, in Aesthetics,Number 8 (March 1998) and my manuscript “19l0nen zengo no Nihon ni okeru Sezanisumu (Sezannu geijutsu no juyo to shokai)” (”Cézannism”,in Japan around the year 1910 [The introduction and reception of Cézanne’s art]), pp. 1-34 of the Report on Research Results for the 1989 Scientific Research Subsidy (Funded Research A), 1990.

- “Kakumei no gaka”in Shirakaba(White Birch), Volume 3, Number 1 (January 1912), pp. 1-31

- See for example Kitaro Nishida’s « Keiken naiyo no shuju naru remoku”(Various continuities in the content of experience) (February, 1919) and “Bi no honshitsu”(The nature of beauty) (March-April, 1920), contained in Nishida Kitaro zenshu dai 3 kan(Complete works of Kitaro Nishida, Volume 3). Tokyo: Iwanami shoten (1965), pp. 99-140; 241-282. See also Iwaki Ken’ichi uNishida Kitaro to geijutsu”(Kitaro Nishida and art) in Nishida tetsugaku senshu dai 6 kan(Selected works of Nishida’s philosophy, Volume 6). Tokyo: Toeisha (1998), 408-437.

4 See Ken’ichi Sasaki’s “Jinkaku to sakuhin– sonohisoshosei ni tsuite”(Personalityand the artwork – concerning their asymmetry) in Bigaku(Aesthetics), Number 134 (1983), pp. 1-12

5 “Seimei no mondai”in Shirakaba(White Birch), Volume 4, Number 9 (September 1913), pp. 1-74

- Midoriiro no taiyo”,in Subaru(The Pleiades), Volume 2, Number 4 (April 1910), 35-41

- Inshoshugi no shiso to geijutsu.Originally published by Tengendo Shobo, reprinted in Zokeibiron (Essays on plastiquebeauty), Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo (1942), 253-415

- Sotaro Nakai, Kindai geijutsu gairon zen.Tokyo: Nishodo (1922)

- Juzo Ueda, Kindai kaiga shi ron.Tokyo: Iwanami shoten (1925)

- See“Keiken naiyo no shuju naru renzoku”(Various continuities in the content of experience), pp. 99- 140

- “Gendai no tetsugaku”(Modem philosophy) (March, 1916), contained in Nishida Kitaro zenshu dai 1 kan(Complete works of Kitaro Nishida, Volume 1).Tokyo: Iwanami shoten (1965), pp. 367-8

- Iwaki, p. 424

- Nakai, 239-268

- Ueda, 54

- “1920 nendai Nihon no jinkakushugi Sezannu- zo no biteki konkyo to sonokeisei ni kansuru shiso oyobi bijutsu seisaku no bunmyaku ni tsuite”(Concerning the aesthetic basis for Cézanne’s Personalist image in 1920s Japan and the ideas related to its formation, as well as the context of artistic production), paper delivered at the regular meeting of the western branch of The Japan Art History Society, Osaka: The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Japan, 25 January 1997

- See also Sadami Suzuki’s “Seimei” de yomuNihon kindai Taisho seimeishugi no tanjo to tenkai (Viewing modem Japan through “life” : the birth and development of Taisho “Lifeism”). Tokyo: NHK publishing, 1996

- Jiro Abe, Jinkaku-shugi,Tokyo: Iwanami shoten (1922)

- See note 15.

- To put it clearly in order to avoid misunderstanding, the artistic theory and criticism of Nishida and Ueda, for example, had new developments following the 1930s, and this is not a judgment on the total body of criticism produced by the critics cited in this essay.

- “Shajitsushugi no sonzai riyu”in the May 1935 edition (No. 363) of the journal Mimeand reprinted in Kindai kaiga to rearisumu(Modem painting and Realism), Tokyo: Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan (1989),pp. 7-13

- “Sezannu to shizen”,originally published in the journal Dowa(Harmony), October 1939 and reprinted in Kindai kaiga to rearisumu(Modem painting and Realism), pp. 206-216

- ^Sezarmu no bigaku’\originally published in the August 1939 issue (No. 416) of Mizueand reprinted in Kindai kaiga to rearisumu(Modem painting and Realism), pp. 195-205

- Emile Bernard, Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne et lettres.Paris (1921), p. 30

- Reprinted in Zokeibiron(Essays on plastiquebeauty), pp. 400-401

- Bernard, ibid” p. 72

- “Shajitsu to Sezannu noe” reprinted in Gaka no me(The eye of the artist), Zayuho Kankokai (1956), pp. 6-8

- Originally published as “Sezannu no e« (Cézanne’s paintings) in the March 1934 (VoL 9, Number 3) issue of Bijutsu(Art); reprinted inGaka no me(The eye of the artist), pp. 92-3

- Originally published in the January 1936 edition (Vol.13, Number 1) of Atorie(Atelier) as “Dehorumashion” (Deformation)reprinted in Gaka no me(The eye of the artist), p.13

- Dorival, Bernard. Les Étapes de la Peinture Française Contemporaine, Tome Troisième: Depuis Le Cubisme1911-1944. Paris (1948), pp. 239-312.

- Ekoru do Pari zen 3 kan.Tokyo: Shinchosha (1950-51)

- See for example Àichi Prefectural Museum et al.,Fovisumu to Nihon kindai yoga(Fauvism and Japan’s modern Western art), (1993); Toshiharu Omuka,Taishoki shinko bijutsu undo no kenkyu(Research on the Avant gardeart movements of the Taisho period), Tokyo: Sukaidoa (1995)

- Junsui kaiga ron.Daisanshoin (1932)

- “Gendai no chokoku”reprinted in Zokeibiron(Essays onPlastiquebeauty), pp.169-250

- “Sozai to zokei”reprinted inZokeibiron(Essays onPlastiquebeauty), pp. 1-74

- , p. 51

- “Nihon ni okeru Sezannu”,originally published in the January 1947 edition (No. 497) of the journalMizue,reprinted inHijikata Teiichi chosakushu 6(Collected works of Tenchi Hijikata, Number 6), Tokyo : Heibonsha (1976),pp, 260-277

- “Sezan, Doran, to Yasui Sotaro- Shajitsu no ichi to seikaku”originally published in the April 1950 edition of the journalAtorie(Atelier), and reprinted inHijikata Teiichi chosakushu 6(Collected works of Teiichi Hijikata,Number 6),pp. 229-237

- “Shajitsushugi no sonzairiyu”,originally published in the May 1935 edition (No- 363) of the journalMizue,and reprinted inKindai kaiga to rearisumu(Modem painting and Realism), p.13.

——————————————————————————————————————————

1930-40年代の日本におけるセザンヌの受容

Cézannisme in Japan 1922•1-1947 •1

平成10-13年度文部科学省科学研究費補助金基盤研究(c) (2)研究成果報告書

[非売品]限定300 部©Takanori NAGA 2002

編集•発行:永井隆則

京都工芸繊維大学工芸学部造形工学科

606-8585京都市左京区松ヶ崎御所海道町

TEL/FAX:075-724-7616 E-mail:t-nagai@kit.ac.jp

発行日:2002年3月31日

印刷:和光印刷株式会社

602-0012京都市上京区烏丸通上御霊前上ル内構町420-3

TEL:075-441-5408 FAX:075-441-4982 E-mail:info@wako-print.co.jp

Cezanne’s Reception in Japan During the 1930-40s

Cézannisme in Japan: January 1922 to January 1947

Report on Research conducted under the Auspices of the Scientific Research Grants for 1998-2001 Base Research (c)(2) by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

Edited by Takanori NAGAI ©Takanori NAGAI 2002(Tel/Fax:81-75-724-7616, E-mail :

t-nagai@ kit.ac.jp)

Printed by Wako Print Ltd.; Kyoto in Japan

Published March 2002 by Takanori NAGAÏ (Kyoto Institute of Technology) in Japan

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.