How Paul Cézanne Rejected the Fini Concept

Takanori Nagaï

(publié dans Appreciating the Traces of an Artist’s Hand, Kyoto Studies in Art History, Volume 2, Department of Aesthetics and Art History, Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University, Kyoto, 2017, pp. 133-148)

Summary

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) was a painter who was active in France from the middle of the Second Empire (1852–1870) through to the Third Republic (1870–1940). During that time, and since the rise of Neoclassicism, the Salon painters of the day heralded and maintained the technical concept of fini, or painting the surface finish, and its accompanying aesthetic standards. Conversely, Cézanne took a diametrically opposed stance as he sought to destroy the fini concept and offer a new technical form and aesthetic.

This paper first introduces the painting theories developed within Neoclassicism, and then analyzes how the aim of fini heralded in Neoclassical painting took on new meaning during the Third Republic due to the commercialism that followed the industrial revolution. Finally, the paper shows that Cézanne honed his desire for a new artistic stance in which art should express “temperament,” individuality,” and even “sensation,” and that in this new aesthetic, he invented original techniques such as the construction of a picture plane through the adroit use of a build-up of pigment (the couillarde technique), brushstrokes (the constructive stroke), and dots (tache), which completely rejected the fini convention.

Introduction

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) was a painter who was active in France from the middle of the Second Empire (1852–1870) through the Third Republic (1870–1940). During that time, and since the rise of Neoclassicism in the mid-eighteenth century, the Salon painters of the day heralded the technical concept of fini, or painting the surface finish, and maintained its accompanying aesthetic standards.

This paper demonstrates how Paul Cézanne rejected the fini concept, though it does not argue this point from the perspective of the non-finite, as this topic has been discussed in detail by many previous scholars[1]Cf. Takanori Nagaï, Le problème de la marge chez Cézanne (Rapport pour le diplôme d’études approfondies, Histoire et Civilisation, Université de Provence), Aix-en-Provence, 1984, pp. 1–61; Felix Buamann et al. (ed.), exh. cat. Cézanne Finished Unfinished, Kunstforum, 2000 ; Takanori Nagaï, “Cézanne and Time,” XVth International Congress for Aesthetics, 2001 (CD-Rom), Tokyo, The Japanese Society of Aesthetics, 2002; Thodore Reff, “La question du fini chez Cézanne« , Mélanges en hommage à Françoise Cachin, Paris, 2002, pp. 194-201..

Rather, this discussion takes the viewpoint of the social history as well as the semiology of art. To my knowledge, no such discussion has been conducted to date.

1. The Fini Concept in Academic Painting

Paul Cézanne sent his mother a letter in 1874 that contained the following passage:

I am beginning to consider myself stronger than all those around me, […] I have to work all the time, but not to achieve the finish (fini) that earns the admiration of imbeciles. And that thing that is so widely valued is nothing more than a workman’s craft, and makes all the resulting work inartistic and common. I must strive for completion purely for the satisfaction of becoming truer and wiser. And believe you me, there always comes a time when one asserts oneself, and one has admirers who are much more fervent and more convinced than those who are attracted only by mere surface[2]Alex Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cézanne, London, 2013, p. 154..

Thus, Cézanne criticized the fini concept that was widely accepted and admired by academic painters of the time.

So, of what did the concept of fini consist? It originated from the techniques and aesthetics of Neoclassicism; therefore, in order to answer this question, I will first introduce and analyze the painting theories developed by Swiss Neoclassical painter Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789) (fig. 1). Liotard traveled to Paris in 1725 to train as a painter under French artists including Jean-Baptiste Massé (1687–1767) and François Lemoyne (1688– 1737).

According to Liotard’s book of art theory, Traité des Principes et des Règles de la Peinture (Introduction to the Principles and Rules of Painting) (1781), the aim of painting is to reproduce nature:

The painting is the immutable mirror which reflects all of the most beautiful things that the universe gives us. […] The painting represents, expresses, and fixes every movement which one can observe in nature […] The painting, for her imitation, is superior to music[3]Jean-Étienne Liotard, Traité des Principes et des Règles de la Peinture, 1781, Genève, 2007, p. 17..

However, brush strokes, dotting (tache), and buildup of pigment on the painting surface (referred to in this paper and in the below quotes as “touches”) are all examples of an artist’s actions, and thus constitute an unnatural presence that does not exist in nature:

In the sublime painting of nature, the whole is related admirably. Every part, even the most disparate, is imperceptibly unified; one does not see at all any touches in works by nature. That is the strong reason why one must not put any touches on the painting. One must not paint by any means what one does not see[4]ibid. p. 37..

Further, Liotard’s ideal is for painting to realize elegance; hence, just as artists would avoid unattractive physical elements such as wrinkles, blemishes, or scars in their depiction of human skin, so too should material elements such as the “touches” mentioned above be completely avoided on the painting surface as, according to Liotard, such elements are offensive to the eye:

The less sensitive, the harder the touches, the more they conduct ugliness. This gives a shock to the eye of a person who, after penetrating the true beauty of nature, wants to find it again in the copies of nature provided by the artist; this ugliness displeases even those who do not have any knowledge about art. Hence, such touches are not only ugly, but are also most distant from nature[5]ibid. p. 37..

The most agreeable qualities in the painting are neatness, cleanliness, and uniformity: but touches are completely contrary to these three qualities; so one must never use touches[6]ibid. p. 40..

What is painted uniformly, neatly, and cleanly gives always much more pleasure to see than what is rugged. Painters who prefer to make roughly prepared paintings on the canvas move away from beauty, one of the qualities of which is unity. If a beautiful woman was attacked with smallpox and the pockmarks remained, then she would be no more accounted among beauties, because her skin would have become rugged and irregular. In every product by a machine, one is proud of the uniformity, the neatness and the cleanliness; these qualities are much more necessary to the painting than to the mechanical. They increase considerably the brightness of the painting as I have already indicated. On the contrary, painters who paint with many touches always convey ugliness, rudeness and roughness, in spite of the merit of their works[7]ibid. p. 50..

In the quote directly above, Liotard compares the ideal beauty of the painting surface not only to the skin of a beautiful woman but also to the bright surface of a mechanical body. Conversely, he finds similarity between a painting surface made up of touches and skin that has been attacked by smallpox. For Liotard, painters who adhere to the former approach include Raphael and Correggio, while the latter comprise Rembrandt, Rubens, and other baroque painters.

Fini thus completely erased the traces of artistic action and the unsightly elements of the subject. Liotard believed that this was an essential and final step in the realization of the artists’ aesthetic ideal, and comprised neatness, cleanliness, uniformity, and brightness —in a word, elegance.

He summed up the fini technique as follows:

The fini is one of the most agreeable parts of the painting. It is very difficult to finish with a good taste. So, works that are finished very well and with good taste are the rarest and most valuable[8]ibid. p. 56..

Fini was also seen as representative of an ethical value. From this point of view, Liotard criticized painters who used many touches:

I admit that there are famous painters whose touches have many expressions, and they indicate nature very well. However, as they don’t have the most precious part, that is to say, the fini, these works please only the painters. In all arts, perfection, as far as imperfect humanity can reach, should be the only end of the artist, as it is the unique true glory. The good painter must also please everybody; and those who get away from there is a mistake: because this way of painting with touches is fallacious, it is adopted and followed only by the impatient, lazy, avaricious painters, and only by those who are not able to finish their paintings very well and who make only rough sketches[9]ibid. pp. 42-43..

In this sense, fini is an ultimate ideal that should be realized through artistic activity, an ideal that is considered closely related to the ethical value of human labors in general.

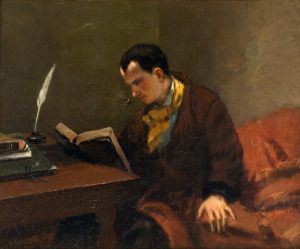

After Liotard, Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) (fig. 2) inherited the fini concept, and also purged touches from his paintings:

Fig. 2 Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, Self-Portrait at the Age of 24, 1804 (revised ca. 1850), oil on canvas, 78 x 61 cm, Musée Condé, Chantilly, Oise.

What is called ‘the touch’ is an abuse of the execution. It is nothing but a quality of poor talents, poor artists, who get away from the imitation of nature in order to simply show their skillfulness. The touch, even if it is very clever, must not be apparent; otherwise, it obstructs the illusion and immobilizes everything. In place of the objects represented, it allows the process to be visible, in place of the thought, it allows the hand to be laid bare[10]Ingres, Écrits sur l’art, Paris, 1994, p.70..

2. The Changing Nature of the Fini Concept during the Third Republic

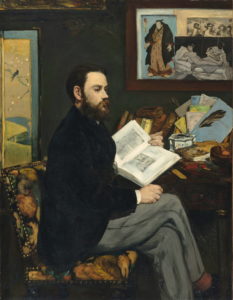

The aim of fini heralded in Neoclassical painting took on new meaning as consumerism rapidly rose in the Third Republic thanks to the Industrial Revolution. Art critic and novelist Émile Zola (1840–1902) (fig. 3) revised the meaning of fini during the Second Empire and this interpretation carried through to the Third Republic. Zola did not use the word fini in his writings on academic paintings, but it is self-evident that what interested Zola among the particularities of paintings of the official exhibition at the time—the so-called Salon—was the characteristics produced by fini, and that he found its meaning to differ from Liotard’s understanding.

Zola criticized paintings in the Salon by academic painters such as Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889), Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), and William Bouguereau (1825–1905), all of whom belonged to the genealogy of Jean-Dominique Ingres’ Neoclassicism. In doing so, Zola exposed the Third Republic Salon painters as using the fini concept in response to the rapidly expanding commercialism of the day: as a symbol for the paintings they used as high-priced commodities aimed at the nouveau riche, or bourgeois. Zola suggested that these painters employed this fini “polishing” in order to remove all traces of the artist’s hand, which could be imagined as slights that would stand as proof of an inferior product.

Responding to the needs of the bourgeois allowed these painters to reap great profits, but at the same time prevented them from displaying their individuality, as it removed all traces of their hands’ unique movement from the surface. According to Zola, fini was an ostentatious pose that these painters assumed in order to attract their bourgeois customers.

Zola criticized Cabanel as follows:

The principal malice of Cabanel is that he reformed the academic style. To the classical old doll, toothless, bald, he gave a false head of hair and a false tooth. He transformed even a wicked woman into a fascinating woman, pomaded, perfumed, playing the coquette, with curly blond hair. The painter was even rejuvenated a little. The female bodies on his canvas became like a cream. […] This mediocre person does his every job faultlessly. He can be original with discretion. He is not of the party of ferocious persons who go to excess. He is always decent. He is always classical after all, he never scandalizes the public, deviating so violently from the conventional ideal. In one of his paintings exhibited this year, he confessed everything. The title is Thamar […] It is a work which has neither fault nor merit; it transmits the most horrible banality; it is a work made with very old formulas, renewed by the clever finger of a craftsman apprentice[11]Émile Zola, Écrits sur l’art, Paris, 1991, pp. 293–294. (fig. 4).

Gérôme is less impressive than Cabanel, but he enjoys great popularity. He is so classical, so academic that he received a prize when Courbet was commanded to pay for the memorial column of the Place Vendôme and exiled. The exhibition gives a complete idea of his art. […] It is just the same work as that by the convict sculpturing the coconuts; his methods are invariable, the results are always similar. But Gérôme has an odder way of making. The touches disappear. The visitors admire his paintings as if they admire the doors of the splendid carriage. There is a triumph of the lacquer; every detail is painted with scrupulous care, and covered so to speak with a glass. Does Gérôme enamel his paintings as if he enamels his drawings on the porcelain? The bourgeois are overjoyed […]. To get much more triumph, Gérôme escapes the weary, rubbish subject matter of Cabanel to pick up the anecdotes. Each of his works is a short-short, some of them are witty, even erotic, but with the tone extra-fine, even playful. Everyone remembers his Phryné devant l’Aréopage. A pretty naked caramel girl is painted, the old men stare into her; the caramel color of her body makes her beauty superficial. At the exhibition of the Champ de Mars, we can see the bathing female women (Les femmes au bain). Some nudes without a stitch of clothing give to the public an innocent pleasure of scrutinizing them with a magnifying glass. For the anecdotes in the painting, naked women are abundantly painted[12]Ibid., pp. 373–374. (fig. 5).

I can call Bouguereau a link between Cabanel and Gérôme, who has both the pedantry of the former and the mannerism of the latter. It is the apotheosis of elegance; an enchanter painter who draws at the same time the celestial creature and candies which melt in the eyes. Excellent talent, if talent is after all the question of skillfulness necessary to flavor nature with this sweet sauce; but his art lacks vigor, vitality, it is painting in miniature exaggerated monstrously, enormously, devoid of all truth[13]Ibid., p. 375. (fig. 6).

Fig. 6 William Bouguereau, The Birth of Venus, 1879, oil on canvas, 71.8 x 122.9 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

In the above quotes, Zola identifies the fini technique in these artists’ works as the a cream-like character in Cabanel, an enamel-like quality in Gérôme, and a sweet sauce in Bouguereau, highlighting the sensual effect on the whole. This collaborates with other elements in the paintings, such as the subject matter and drawing techniques used[14]Cf. Ernst.H. Gombrich, “La psychanalyse et l’histoire de l’art,” L’Ēcologie des images, Paris, 1983, pp. 45–79..

If I painted like Bouguereau, I would be able to gain much money, but the public does not change at all, they love only the sweet and smooth painting[15]Vincent van Gogh, Les Lettres, volume 4 (Arles, 1888–1889), Amsterdam, 2009, p. 232..

The aspects that van Gogh considered effective with respect to appealing to the public are precisely those of the fini concept. As van Gogh suggested, there is no doubt that the academic painters took advantage of the effect of fini as a strategy to sell their paintings.

So, amidst what kind of social milieu did these painters choose this strategy? First, the changing nature regarding the institution of the official exhibition was a factor : the Salon, which, at the beginning of the seventeenth century only accepted members of the Academie des Beaux-Arts, was opened up not only to painters who were not part of the academy but also to foreign painters following the French Revolution, and then came under private management in 1881. The second factor of influence was the changing clientele : in the years following the Industrial and French Revolutions, in place of royalty and titled nobility, new bourgeois such as large merchants, businessmen, statesmen, government officials, doctors, and lawyers came to comprise society’s upper class[16]Cf. T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, London, 1984..

These changes gave rise to the variety of tastes conveyed by the works exhibited at the Salon, which ultimately revealed a loss of the prior leading fashions. With this democratization of the Salon system, as well as the decline of humanistic culture, academic painters became obliged to paint what would sell to the many and unspecified persons who had replaced the old governing class. This kind of public was attracted to paintings much more for their apparent beauty than for the traditional culture conveyed through their subject matter. These paintings had to be polished up via fini like high-grade jewels, because items promoted through the Salon were expected to be expensive, and were hence a sign of the distinguished social status of the new bourgeois.

Zola compared the exhibition space of the Salon to a bazaar, or market[17]Zola, op. cit. (note 11), p. 270.. In fact, many department stores, such as Le Bon Marché (1852), La Samaritaine (1869), and Galeries Lafayette (1893) opened one after another in Paris from the middle of the Second Empire throughout the Third Republic. In addition to this consumption revolution[18]Cf. Rosalind H. Williams, Dream Worlds: Mass Consumption in Late Nineteenth-Century France, Berkely, 1982., thanks to the frequent international expositions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Paris, the city developed as the center of material flow in Europe. Zola pointed out that Salon paintings came to be considered important export objects from France to foreign countries. Undoubtedly, this development of commercialism urged the academic painters to change the function of fini into a means of “seducing” the public into purchasing their paintings. It is no wonder, then, that the advertising industry developed rapidly at the end of the nineteenth century, using means such as posters to advertise various articles. In addition, Henri Zerner (1939–) reported that images of the Salon paintings were often converted into items used for packaging design and other marketing merchandise[19]Charles Rosen and Henri Zerner, “L’Antichambre du musée du Louvre ou l’idéologie du fini,”, Critique, vol. 30 (no. 329), 1974, pp. 859–874..

In a letter to his mother, Cézanne called the public who admired Salon paintings “those who are attracted only by mere surface (ceux qui ne sont flattés que par une vaine apparence)”[20]Recueillie,annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Cézanne Correspondance, Paris, 1978, p. 148.. It is notable that Cézanne used the French equivalent of “flatter” in the original quote. This word has, as synonyms, the expressions passer de la pommade à quelqu’un or cirer les bottes à quelqu’un, both of which mean using one’s “brilliant” appearance to attract the attention of another. Thus, Cézanne felt that fini was a way to attract or flatter the bourgeois for money. An invariable rule of business is that in order to please a client, one must be faithful to their desires and not disturb them by unduly expressing oneself. It is based on this understanding that touches, which express the painter rather than respecting the presence of the client, should be banished.

3. Cézanne Rejects the Concept of Fini

Cézanne took a diametrically opposed stance to the academic approach as he sought to destroy the fini concept and offer a new technical form and aesthetic. He took the Romantics Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) (fig. 8) and Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) as his personal role models and, through intimate debates with his close personal friend Zola, honed his desire for a new artistic stance in which art should express temperament, individuality, and even sensation.

The artist, the true artist, the true poet has to paint only according to what he sees, what he feels. He must be truly faithful to his own nature. As he must escape death, he must avoid borrowing the eyes and the feelings of another person, even if he is so great. Because what he would make from the borrowing, would be for him falsehoods, not realities[21]Charles Baudelaire, “Salon de 1859,” Curiosités Esthétiques L’Art romantique, Paris, arnier, 1962, p. 321..

Zola, inheriting Baudelaire’s idea of art, defined art as follows:

I accept only the individualities, really individual, clearly distinguished. I hate every school, because a school just means the denial of liberty of the human creation. In a school, there is a man, that is, a master. His disciples naturally become his imitators. So, I admit no more realism than other schools. There is truth, or life, but in particular, there are various bodies and spirits, who differently interpret nature. The definition of art would be nothing but this one: A work of art is a corner of creation seen from a temperament[22]Zola, op. cit. (note 11), pp. 124–125..

Throughout his life, Cézanne read with pleasure Baudelaire’s writings and it is clear that the following criticism against a younger artist, Émile Bernard (1868–1941), was founded on Baudelaire’s aesthetic:

In his drawings he produces nothing but old-fashioned rubbish that smacks of the dreams of art prompted not by excitement at nature but by what he has seen in museums, and even more by a philosophical turn of mind that comes from knowing too well the masters he admires. […] Clearly one must experience things for oneself and express oneself as best one can[23]“Letter of Cézanne to his son,” Aix, 13 September 1906, Danchev, op. cit. (note 2), pp. 371–372..

What kind of techniques did Cézanne use to realize his ideal? First, in the couillarde technique he developed during his early period, Cézanne emphasized the materiality of the paint pigments and his hand movements in an effort to show off “masculinity” and “fervent individual sentiments,” thus fiercely opposing the Salon artists’ aesthetic values of paintings that were elegant and refined (figs. 9–10).

In the couillarde technique, Cézanne transferred the paint pigments directly onto the canvas using a palette knife, and extended them in various directions with the power of his fingers, hands, and arms to finally cover the intended area through several facet-like elements. This was modeled on the work of plasterers and allowed Cézanne to transmit in his work not only the movement of his physique, but also of his emotions. The more irregular, the more rugged the paint surface, the more clearly it expressed his strong passion. The word couillarde comes from the word couille, which translates to “testicles,” the symbol of the male. Thus, couillarde literally means “big testicles.” Cézanne’s naming and practice of this technique was intended to antagonize the Salon painters[24]Cf. Ambroise Vollard, Paul Cézanne, Paris, 1919, p. 30; Gustave Coquiot, Paul Cézanne, Paris, 1919, pp. 62–63; Nina Maria Athanassogolou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence: The Painter in His Culture, Chicago and London, 2003, pp. 26–28; Jean-Claude Lebensztejn, “Les couilles de Cézanne,” Ētudes cézanniennes, Paris, 2006, pp. 7–24.. In fact, Zola, a close friend of Cézanne during the 1860s and 1870s, when Cézanne was using the technique, called the Salon painters eunuques— eunuchs; that is to say, males who had lost their testicles, who had ceased to be male[25]Zola, op. cit. (note 11), pp. 122, 135..

While the metaphorical meaning entails the loss of masculine sexual vigor or physical power, the true meaning pertains to a lack of courage to express oneself to others; an absence of enthusiasm to exploit one’s own passions, proper style, or original technique without repeating those already accepted by the public and authorized as the norm. To gain material interest, then, these “eunuchs” were seen by Cézanne to flatter the bourgeois, readily hide themselves, and crush to death their own sensations. It is evident that Cézanne exploited his couillarde technique through his close relationship with Zola and held in common the latter’s criticism of art against the academic paintings.

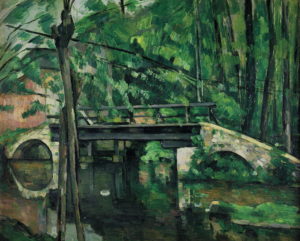

Fig. 11 Paul Cézanne, Brigde of Maincy, 1879–1880, oil on canvas, 58.5 x 72.5 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Second, after having learned the aesthetics and techniques of impressionism at the beginning of the 1870s, Cézanne invented a new technique that he named the “constructive stroke”[26]Theodore Reff, “Cézanne’s constructive stroke,” Art Quaterly, vol. XXV, n. 3, Autumn, 1962, pp. 214–227. (fig. 11). In this he aimed to convey on the canvas the sensations he derived from perceiving nature, transmitting them as oblique, parallel, small touches. Thus, he brought order to the chaos of sensations stimulated by his contact with nature, so that the autonomy of the painting could be realized independently from nature. Hence, he transcended impressionism more rapidly than many of the painters of his generation, and thereby established his originality.

Fig. 12 Paul Cézanne, Forest; Landscape, 1900–1902, oil on canvas, 81 x 64.5 cm, Fondation Beyeler, Basel.

Third, in his final period, Cézanne renewed this approach to painting. He invented the technique of creating compositions through dotting, known in French as tache (fig. 12). These dots were bigger and flatter elements than the constructive stroke, allowing his images to become much more independent from a true representation of nature.

Through these steps, it can be seen that Cézanne relied not upon an already established way of seeing and constructing paintings, but rather upon respecting both forms of sensation; that is, one receiving sensorial data from nature (in Cézanne’s terms, sensation colorée)[27]Émile Bernard, “Paul Cézanne,” L’Occident, nr. 6, 1904 Juillet, p. 20., and the other using this data to form one’s own personal image on canvas (sensation colorante)[28]Ibid., p. 21; Rewald, op. cit. (note 20), pp. 304–305, 308, 318.. Cézanne believed that he could express his whole existence through this process of creating a painting through these small elements—in other words, through his small sensations.

Cézanne’s thesis of art is as follows:

So, the thesis to be expounded—whatever our temperament or strength in the presence of nature—is to give the image of what we see, forgetting everything that has appeared before us. This, I think, should allow the artist to give his whole personality, big or small[29]“Lettre of Cézanne to Ēmile Bernard,” Aix, 23 Octobre 1905, Danchev, op. cit. (note 2), p. 355..

4. Conclusion

Around the end of his life, in 1905, Cézanne communicated to Émile Bernard (once, in fact, the object of his reproach) his criticisms of Salon paintings, as follows:

If the official Salons remain so inferior, it is because they employ only more or less commonplace procedures. It would be better to introduce more personal feeling, observation and character. The Louvre is the book from which we learn to read. However, we should not be content with holding onto the beautiful formulas of our illustrious predecessors. Let us go out to study beautiful nature, let us try to capture its spirit, let us seek to express ourselves according to our individual temperaments. […]Only old residues block our intelligence, which needs spurring on[30]“Letter of Cézanne to Ēmile Bernard,” Aix, Vendredi, 1905, ibid., p. 353..

Thus, the techniques of academic paintings, including fini, seemed to Cézanne to all be commonplace—in other words, old residues—because they lacked personal feeling, observation, character, and individuality. In this way, Cézanne criticized the falsehood and fragility of Salon paintings that sold the artist’s soul in response to commercialism, and in their place presented a new artistic way of being that sought—citing an expression from Cézanne’s letter to Bernard—“truth in painting (la vérité en peinture)”[31]“Letter of Cézanne to Ēmile Bernard,” Aix, 23 Octobre 1905, ibid., p. 356; John Rewald, op.cit. (note 20), p. 315. ; in other words, the imprimatur of the individual. This is the means by which Paul Cézanne rejected the fini concept.

Photo Credits and Sources (de l’article publié dans le Kyoto Studies in Art History)

Fig. 1 (http://www.new-york-art.com/old/Mus-frick-SwissMasterLiotard.php); fig. 2 (https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Auguste-Dominique_Ingres); fig. 3 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ %C3%89douard_Manet), fig. 4 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alexandre_cabanel,_ thamar,_1875,_01.JPG), fig. 5 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me), fig. 6 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William-Adolphe_Bouguereau), fig. 7 (http://www.salvastyle. com/menu_impressionism/gauguin_gogh.html); fig. 8 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_ Courbet), fig. 9 (http://cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/index.php), fig. 10 (http://cezannecatalogue. com/catalogue/index.php), fig. 11 (http://cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/index.php), fig. 12 (http://cezannecatalogue.com/catalogue/index.php).

Notes

Références

| ↑1 | Cf. Takanori Nagaï, Le problème de la marge chez Cézanne (Rapport pour le diplôme d’études approfondies, Histoire et Civilisation, Université de Provence), Aix-en-Provence, 1984, pp. 1–61; Felix Buamann et al. (ed.), exh. cat. Cézanne Finished Unfinished, Kunstforum, 2000 ; Takanori Nagaï, “Cézanne and Time,” XVth International Congress for Aesthetics, 2001 (CD-Rom), Tokyo, The Japanese Society of Aesthetics, 2002; Thodore Reff, “La question du fini chez Cézanne« , Mélanges en hommage à Françoise Cachin, Paris, 2002, pp. 194-201. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Alex Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cézanne, London, 2013, p. 154. |

| ↑3 | Jean-Étienne Liotard, Traité des Principes et des Règles de la Peinture, 1781, Genève, 2007, p. 17. |

| ↑4, ↑5 | ibid. p. 37. |

| ↑6 | ibid. p. 40. |

| ↑7 | ibid. p. 50. |

| ↑8 | ibid. p. 56. |

| ↑9 | ibid. pp. 42-43. |

| ↑10 | Ingres, Écrits sur l’art, Paris, 1994, p.70. |

| ↑11 | Émile Zola, Écrits sur l’art, Paris, 1991, pp. 293–294. |

| ↑12 | Ibid., pp. 373–374. |

| ↑13 | Ibid., p. 375. |

| ↑14 | Cf. Ernst.H. Gombrich, “La psychanalyse et l’histoire de l’art,” L’Ēcologie des images, Paris, 1983, pp. 45–79. |

| ↑15 | Vincent van Gogh, Les Lettres, volume 4 (Arles, 1888–1889), Amsterdam, 2009, p. 232. |

| ↑16 | Cf. T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, London, 1984. |

| ↑17 | Zola, op. cit. (note 11), p. 270. |

| ↑18 | Cf. Rosalind H. Williams, Dream Worlds: Mass Consumption in Late Nineteenth-Century France, Berkely, 1982. |

| ↑19 | Charles Rosen and Henri Zerner, “L’Antichambre du musée du Louvre ou l’idéologie du fini,”, Critique, vol. 30 (no. 329), 1974, pp. 859–874. |

| ↑20 | Recueillie,annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Cézanne Correspondance, Paris, 1978, p. 148. |

| ↑21 | Charles Baudelaire, “Salon de 1859,” Curiosités Esthétiques L’Art romantique, Paris, arnier, 1962, p. 321. |

| ↑22 | Zola, op. cit. (note 11), pp. 124–125. |

| ↑23 | “Letter of Cézanne to his son,” Aix, 13 September 1906, Danchev, op. cit. (note 2), pp. 371–372. |

| ↑24 | Cf. Ambroise Vollard, Paul Cézanne, Paris, 1919, p. 30; Gustave Coquiot, Paul Cézanne, Paris, 1919, pp. 62–63; Nina Maria Athanassogolou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence: The Painter in His Culture, Chicago and London, 2003, pp. 26–28; Jean-Claude Lebensztejn, “Les couilles de Cézanne,” Ētudes cézanniennes, Paris, 2006, pp. 7–24. |

| ↑25 | Zola, op. cit. (note 11), pp. 122, 135. |

| ↑26 | Theodore Reff, “Cézanne’s constructive stroke,” Art Quaterly, vol. XXV, n. 3, Autumn, 1962, pp. 214–227. |

| ↑27 | Émile Bernard, “Paul Cézanne,” L’Occident, nr. 6, 1904 Juillet, p. 20. |

| ↑28 | Ibid., p. 21; Rewald, op. cit. (note 20), pp. 304–305, 308, 318. |

| ↑29 | “Lettre of Cézanne to Ēmile Bernard,” Aix, 23 Octobre 1905, Danchev, op. cit. (note 2), p. 355. |

| ↑30 | “Letter of Cézanne to Ēmile Bernard,” Aix, Vendredi, 1905, ibid., p. 353. |

| ↑31 | “Letter of Cézanne to Ēmile Bernard,” Aix, 23 Octobre 1905, ibid., p. 356; John Rewald, op.cit. (note 20), p. 315. |