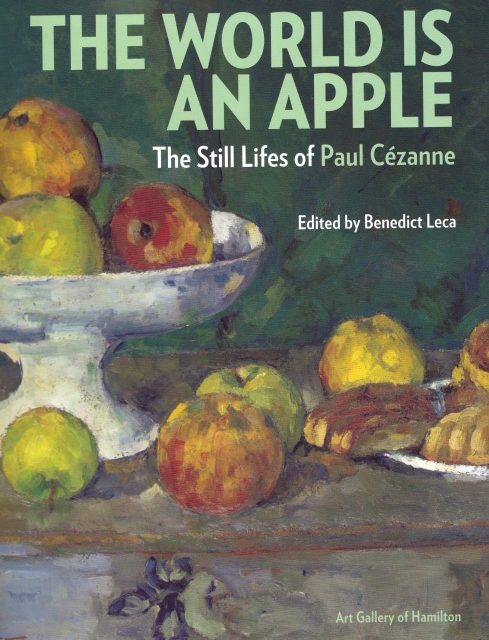

The World is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cezanne

la Fondation Barnes à Philadelphie (USA) présente sous ce titre du 14 juin au 22 septgembre 2014 une exposition de natures mortes de Cezanne. Cette exposition est ensuite exposée à The Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada du 1er novembre 2014 au 8 Fevrier 2015

*

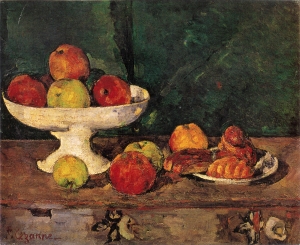

Premiering at the Barnes Foundation, this tightly curated exhibition charts a thematic and chronological sweep of Cezanne’s still-life painting, showing how the “Master of Aix” recast the genre and set it on a new course. Traversing the breadth of his still-life production—from early paintings engaging with past masters to very late works unique to him, and treating a range of themes including apples, flowers, and skulls—this select gathering of paintings offers viewers a brief reappraisal of Cezanne’s monumental achievement in this genre.

Cezanne’s art remains central to enduring concerns of art making, touching on materiality and representation, as well as on the interpretive foundations of art history itself. Comprising 21 Cezanne masterpieces, The World Is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cezanne seeks to render succinctly the richness and novelty of still lifes created by an artist of rare intuition and unerring aesthetic sensibility.

Curator : Benedict Leca, Director for Curatorial Affairs, Art Gallery of Hamilton

Coordinating Curator for the Barnes Foundation : Judith F. Dolkart, Deputy Director of Art and Archival Collections and Gund Family Chief

***

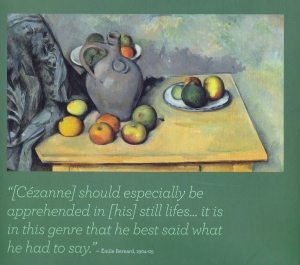

Paul Cezanne had a charged relationship with objects: they seemed to him to be alive, interactive in their engagement with other things and people, and in turn ready material for his painterly vision. Cezanne himself spoke of “sugarpots with a soul,” and the painter Emile Bernard remarked that “any platter, fruit, glass or any object…[elicited Cezanne’s] commentary and reflection.”

The proposed exhibition departs from this juncture of art and the objects of everyday life to offer a reappraisal of Cezanne’s achievement in the genre of still life. For it can be said that Cezanne set still life painting on a new course, one that redrew still life’s purview away from the inert symbolism of things and recast the genre as formative to all others.

According to Joachim Gasquet Cezanne “processed his perception of things through still life.” And so Cezanne set about sensing, analyzing and depicting forms and objects as individual units that might “interpenetrate one another,” creating signal still lifes whose unconventional spaces, allusive juxtapositions, and demonstrative handling expanded the discursive field of things, unmooring forms and objects from the rules governing normative experience. Cezanne routinely trespassed across genre lines, shaping objects to evoke bodily forms, perceiving skulls as apples. Thus, although Cezanne was varied in his treatment of still life throughout his long career, it is nonetheless a synthetic apprehension of Cezanne’s still life oeuvre that the exhibition proposes, one coincident with the synthetic view of Cezanne’s methodology it argues for.

This ‘holistic’ approach to still life painting was also in itself a calculated course, one that set out a narrative—as per the artist himself—of Cezanne’s own transcendence in the genre. Cezanne’s sensory practice was self-ascribed and performed, a performance for which still life was the ready medium, of a piece with Cezanne’s own varied selfdefinition as an artist. Cezanne’s engagement with still life was in this way a selffulfilling journey of self-discovery, where novel depictions—using things enlivened with improbable properties—should stand in for the artist’s own ever-evolving sensory aesthetic. The conceptual design and physical manipulation of objects would thus define his artistic vision, making a synthetic assessment of his output in still life a study into what Cezanne himself disavowed: a Cézannian aesthetic of still life and of his painting more broadly.

Cezanne was as systematic as he was wide-ranging in his approach to still lifes; and he painted them in every graphic media. The proposed exhibition presents a selection of mostly paintings to chart both a thematic and chronological sweep of Cezanne’s still life painting. He traversed the genre: from learned adaptations of past masters to minute, painterly sketches, to large experimental paintings. He also insistently returned to particular things across decades: skulls, apples and pottery. Cezanne’s art nonetheless remains for all times concerned with the problems of representation, and his path breaking still lifes offer us insights into the creative processes of an artist of intuitive talent, whose creations broach both sensory experience and the critical attention to the practice of representing, to the problems of representation.

With no claim to an exhaustive or definitive appraisal, the exhibition thus seeks to render the fullness of Cezanne’s still life practice in five interrelated thematic sections, each in turn presented chronologically.

Still Life and the Meaning of Things

Cezanne defined himself by means of his surroundings: things were alive and transmuted into a visual language rich with optical and tactile effects, formal equivalences and symbolic allusions. Everyday objects were for Cezanne significant ciphers of place—whether Provence or Paris—and of a personal history in large part anchored to family. The world of things and Cezanne’s own deeply personal and sensory approach to art making in reaction to it shaped the nature of his formal experimentation.

Subjectivity and Tradition

Still life painting was an important conduit for Cezanne’s processing of tradition on his way to creating his own artistic persona in the metropole. He continuously absorbed the lessons of past masters, first seeking notoriety in confronting tradition through willfully demonstrative, comparatively radical painting. Integrated in the Parisian art world, Cezanne engages contrasting figures such as Pissarro and Manet—who were themselves reacting to the Old Master tradition—through a small number of still life masterpieces of a more refined handling that announce Cezanne’s mature works

Cezanne and the Living Objects of Still Life

Cezanne created a complex body of still life painting during the years of his mid and late career. He articulates a highly personalized still life practice rooted in sensory effects, creating works that probe illusion, the properties of paint, the relationship of figure to ground, of viewer to painting. Meandering across registers of meanings, Cezanne appropriates, reassesses, adapts given motifs or themes or formal arrangements.

- The 1870’s, a “period of groping” if we extend Zola’s famous description of Cezanne’s achievement to the entire decade, characterized in his still life painting by an enduring classicizing impulse, especially early in the decade, and by more adventurous experimentation at its end.

- Group “with wall paper”: rumination on space and its illusion, the materiality of paint, and representation.

- the 1890s (pair): color, structure and the landscapes of still life.

- Plaster cupid: the body as still life element in the process of painting.

- Still Life in the late years: surface and the conflation of space

- Hommage: the meanings of Cezanne’s painting

Cezanne’s Apples

Cezanne’s sensory effects, his cogitations on touch and objecthood, are resumed in his many vigorously touched paintings of apples, talismanic fruits that for him embodied a rich symbolism conjoined to a compact physical geometry adaptable to the formal logic of a painting or drawing. Cezanne himself vowed to “astonish Paris with an apple,” and the recurrence of apples and red orbs, and his emphasis on tactile effects to render graspable fruit, evidence their import in his imaginary.

Skulls and the Prospect of Death

Mortality remained an enduring thematic in Cezanne’s art, just as it was the cause of irrational fears in his actual life. A skull—like an apple—was a ready-made motif, but one peculiarly suited to associations beyond the tactile or purely sensory of the apple. Laden symbolically, and as forms readily adaptable to visual puns, skulls enabled Cezanne to mobilize traditional symbolism to express the considerable skepticism—if not melancholy—that accompanied his artistic enterprise.