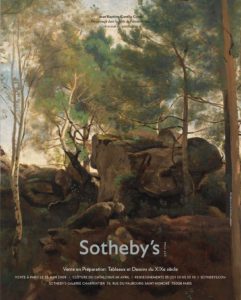

R775 – Rochers à Fontainebleau, 1897-1898 (FWN322)

Pavel Machotka

(Cliquer sur les images pour les agrandir)

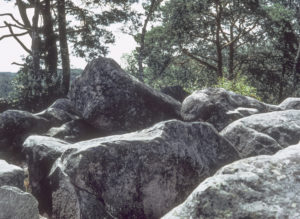

The rock formations in the forest of Fontainebleau stir the visitor’s imagination. Some arouse us by their fantastic, animate shapes, but those are hardly candidates for a Cézannian analysis; others, however, violet-grey, inanimate and huddled together in massive groups, invite a subtle study of the elaborate interrelations of volumes and closely adjoining tones. Such is the group of rocks in Rochers à Fontainebleau, and the similar group in the photograph (where the granite, the lighting, and the short segment of flat horizon, identify the region — but alas not the group itself).[1]

Cézanne worked in the forest in 1897 and 1898, and the patches resemble those of other paintings done about then that may well be the date for this picture.

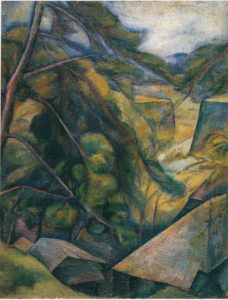

In the surfaces of the rocks, Cézanne’s late patches are set down so as to overlap; the lower patch covers the upper one, and a series of these overlaps creates a receding surface, as in most of the rocks here. The central stone has a flat surface facing us, however; Cézanne signals this with patches that all lie in the same plane. But the patches do much more than just represent surfaces, whether flat or curved. Since they must be of different hues if they are to remain distinct, Cézanne can also use a single set of hues, in different proportions, to represent quite different colors – those of rocks and trees as here, for example. Red-browns, grey-greens, greys, grey-violets, and other half-tones, are the material of which the surface is built here, with the rocks simply given less green (but some nevertheless) and the trees less violet (but still some). The technique is related to that of his watercolors but is adapted to the properties of oil: the patches remain opaque and create solid, rounded objects.

This brief description of the technique is far from a digression; it is vital to describing the aesthetic effect of Cézanne’s late landscapes. The Rochers picture is a thoughtful and somber painting, certainly; it captures the deeply congested, stifling atmosphere that can be felt in some parts of the forest; but it is also testimony to a profound desire to render the unity of a small corner of nature, to display painting‘s particular strength in creating a believable analog of that world, and — although it may not have been intended as such – to reveal the painter’s complex understanding of the interwoven relationships of things. And the remarkable thing is the risk that Cézanne has taken: far from enticing us into the painting by the promise of a happy place or the pleasure of brilliant color, he has held us at a distance with its dark mood. We admire the painting more for what it achieves so thoughtfully than for what it might promise sensually.

The composition is centered by a richly painted mound in Naples yellow, which is separated from the surrounding objects by a thick, undulating outline; this singular shape provides relief from the massive austerity of the rocks and restores warmth to the color balance. To contain the massive leftward thrust of the rocks, Cézanne opens the sky to the left of center and takes care to stop the movement at the left edge, with a thin tree which pushes back. The result is a resolution which recognizes and respects the tensions it must resolve: the painting is quintessentially Cézannian in its pictorial dynamics and particularly subtle in its means of achieving them.

Source: Machotka, Landscape into Art

[1] Three guides with intimate knowledge of the huge forest kindly accompanied me in my search in 1977, but our excursion proved fruitless. The group of rocks may have been quarried; the guides thought that if it still existed, they would have come upon it.

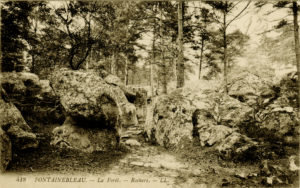

Une carte postale du début du siècle :

Un thème qui a inspiré beaucoup d’artistes tout au long du siècle, par exemple :