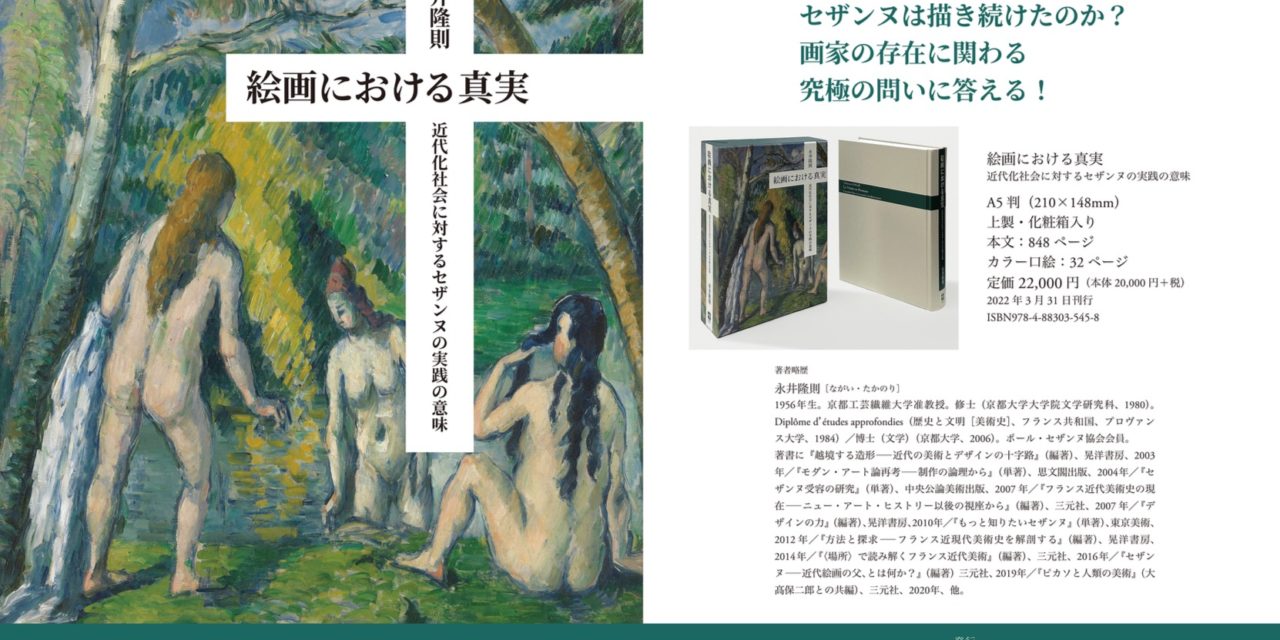

Truth in Painting: The Meaning of Cezanne’s Practices for a Modernizing Society

Takanori Nagaï

Voici le résumé (en anglais) du dernier ouvrage résumant les thèses de Takanori Nagaï relatives à l’influence du contexte historique et social sur l’oeuvre de Paul Cezanne (on trouvera le prospectus correspondant en japonais à la fin du résumé).

Ce livre se situe dans la ligne d’interprétation socio-historique de l’oeuvre du peintre ouverte par Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer [1]Nina Maria Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence The Painter in His Culture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2003, visant à dépasser ou compléter les interprétations plus traditionnelles s’attachant à l’approche biographique, à l’analyse formelle des oeuvres ou à leur interprétation psychologique ou psychanalytique. Il synthétise l’ensemble des diverses études de M. Nagaï consacrées à cette thématique, dans une recherche constante de mettre en évidence l’originalité propre d’un peintre nullement soustrait aux influences et courants artistiques, philosophiques ou intellectuels de son temps, à contre-courant des stéréotypes fréquents qui voudraient que l’oeuvre de Cezanne soit née sui generis, un OVNI en quelque sorte hors sol et hors de tout contexte, par un pur effet du génie unique et foncièrement original de son auteur. L’auteur conclut d’ailleurs que loin d’être le fruit d’un génie asocial ou érémitique, son oeuvre constitue en fait une forme éminente de participation à la vie sociale de son temps.

Table of Contents

Section I — The Life and Works of a Painter in Search of “Truth in Painting”

Section II — Cezanne as Creative Subject

Chapter 1 — Cezanne’s View of Art as Seen in his Letters

Chapter 2 — The Female Image as Arcadia

Chapter 3 — Refuting the “fini” Concept and Realization of “Truth in Painting” concept

Section III — Cezanne’s Artistic Milieu

Chapter 1 — “Artist »

Part 1) Dialogue with Past Masters

Part 2) Impressionist Aesthetic and Cezanne Part 3) Cezanne’s Aesthetic Solidarity with Rodin

Chapter 2 — “Critic »

Part 4) Zola’s Art Criticism as Social Participation

Part 5) Establishment of Artistic Views as a Joint Process with Zola

Chapter 3 — “Collector » Part 6) Collector

Chapter 4 — “Decorative Artists and Designers » Part 7) Art Nouveau and the Vitalism Philosophy Part 8) Cezanne and Modern Design

Section IV — Cezanne’s “Places »

Chapter 1 — “Terroir/Land »

Part 1) The Meaning of Living in Paris: The Dialectics of Art and Nature

Part 2) Cezanne’s Arcadia — Provence

Part 3) The Original Meaning of Cezanne’s Paintings at Jas du Bouffan

Chapter 2 — “Society »

Part 4) The Potential for Cezanne Social History Research

Part 5) The Meaning of “Réalisation des sensations” in a Modernizing Society

In Conclusion

Overview

“Je vous dois la vérité en peinture et je vous la dirai.” (I owe you the truth in painting and I shall tell it to you.) [To Émile Bernard, Aix, October 23, 1905] [2]Paul Cézanne Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald Nouvelle édition réviée et augmentée, Bernard Grasset Éditeur, Paris, 1978, p. 315.

This book summarizes my own “Cezanne theory,” considering the arts of Paul Cezanne (1839- 1906) from the standpoint of social history research and how the world affected his arts.

Cezanne is called the father of modern art, renowned for his massive influence on numerous artists at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Consequently, he has been the subject of voluminous research in the intervening years. I would like to first explain the stance I have taken for my Cezanne theory as developed in this book within the history of such research and scholarly directions both in Japan and overseas.

In essence, Cezanne research has been conducted from the following vantage points.

1. Positivism: As represented by the research of John Rewald (1912-1994), whose work began in the 1930s, this approach assembled and organized the facts about Cezanne’s life and works.

2. Formalism: This approach begun in the 1910s by the English critics Roger Fry (1866-1943) and Clive Bell (1881-1964) was then taken up in the 1930s by the Americans Alfred H. Barr Jr. (1902- 1981), Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) and Clement Greenberg (1909-1994). American critics and art historians such as Erle Loran (1905-1999) and William Rubin (1927-2006) carried it to the present day and it is being further developed today in the work of Yve-Alain Bois (b. 1952), Richard Shiff (b. 1943) and others. This methodology focuses on understanding and explicating how Cezanne’s innovative approach brought about the complete reformation of “forms. »

3. Psychoanalysis: Starting around the 1960s, this method begun by the Americans Meyer Schapiro (1904-1996), Theodore Reff (b. 1930) and others focused on Cezanne the person and his own personal emotional world, elements ignored by formalist study, as it sought to interpret the meanings and emotions hidden in Cezanne’s paintings.

Of these three, formalism has been the overwhelmingly main trend throughout the long history of Cezanne research. This dominance is based on the historical valuation of Cézanne as having shown later generations the new potential for “seeking out the autonomic order of forms on the picture plane,” liberated from the replication of nature. Within the modernist view of history, Cezanne has come to be called the father of modern art, the patriarch of the lineage of new painting (modern art), which stretches from Cezanne to the modern and contemporary eras. The third of these approaches, psychoanalysis, criticizes the formalist approach for only seeking out purely formal elements in Cezanne’s paintings and clarifies how Cezanne’s unconscious, instincts and other driving forces impelled his formal search. In the end, both the formalist and psychological methods consider Cezanne within the same paradigm, seeing Cezanne’s artistic production as events within Cezanne’s own internal world.

In response to these three methodologies, in 2003 Nina M. Athanassoglou-Kallmyer (b. 1945) proposed a fourth. Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer received her doctorate from Princeton University (Department of Art of Archaeology) with a thesis entitled French Images from the Greek War of Independence. Art and Politics under the Restoration, 1821-1830 (Yale University Press, 1989). She is currently Professor Emerita at the University of Delaware (USA). The following book based on her Cézanne and Provence The Painter in His Culture (University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2003) brought about a paradigm shift in Cezanne studies.

In the form of a protest against formalism, she clarified that Cezanne’s oeuvre was rooted in the place of his birth, the topography, climate, customs, history, culture and philosophical environment of Provence in southern France. She further stated that Cezanne’s sudden fame in his late years was based on the fact that he was seen as the personification of “Provence aesthetics” amidst the growing regionalist movement that embroiled every region of France as those regions rebelled against the post French Revolution strengthening of centralized power and its corresponding enforcement of standardization across France as a whole.

Thus, Athanassoglou-Kallmyer’s method is part of the social history of art research methodologies. While social history research itself had a long tradition in America starting with Meyer Shapiro’s heralding of the method in the 1940s, followed by the work of such scholars as Linda Nochlin (1931-2017), Robert L. Herbert (b. 1929) and Timothy James Clark (b. 1943). I believe that this approach had never been applied to Cezanne until Athanassoglou-Kallmyer’s workfor the following three reasons. First, Cezanne’s evaluation has been based in the firm modernist formalist value system. Next, the “master painter Cezanne,” “recluse Cezanne” images have been widely disseminated as the myth of Cezanne as a painter who had no interest in the time or society in which he lived, turning his back on such as he spent his life pursuing his own artistic vision. Finally, there are very few extant comments by Cezanne himself about the period and society in which he lived.

This book – Truth in Painting: The Meaning of Cezanne’s Practices for Modernized Society – is also based in the new paradigm pioneered by Athanassoglou-Kallmyer. And yet, in the following ways the book is also my own original experiment.

1. Some believe that Athanassoglou-Kallmyer has diluted research on the plastic values that have been previously emphasized by modernist formalism. In this book, I take as reference the methodology of Richard Shiff who uses a formalist stance to make suggestions to social history research, and by demonstrating that Cezanne sought his various values within his social environment, I reposition those values in the foreground of his artistic development.

2. I clarify the process by which Cezanne sought and defined his own unique artistic proposition, namely “the search for truth in painting,” as he positioned himself within his own period environment. In particular, I make note of Cezanne’s artistic environment which included his dialogues with past masters gained through viewing works at the Louvre and other museums; his shared artistic struggle with the artists, critics and collectors of his own period, and his sense of contemporaneity with designers and decorative artists.

3. I focus on the “places” where Cezanne worked. In detail, this was not only in his birthplace of Provence, I also searched for the wellspring of Cezanne’s art theory and thought formation in the dialectic relationship between the two places, Paris and Provence, and clarified the social meaning inherent in such development.

4. Cezanne did not turn his back on the then modernizing society and times in which he lived, rather, he confronted the various problems that he discerned in modernizing society through his pursuit of “truth in painting,” and I concluded that he participated in society in that sense.

This book is the compilation of the following research conducted since 2012 through funding by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science’s Grants in Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) and research funding from non-governmental sources.

1. “Anti-Modernist Thought in Cezanne” (KAKEN Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research, 2012-2014)

2. “General Research on Cezanne’s Theory of Art” (KAKEN Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C), 2015-2018)

3. “Research on the Theory of Art on the Utopique Image in the Post-Impressionism” (KAKEN Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C), 2019-2021)

4. “Research on the creative impact of the Aix-en-Provence milieu, especially that of Cezanne’s home in Jas de Bouffan, on the development of Cezanne’s art ” (The Kajima Foundation for the Arts, Support for International Exchanges, 2019)

To mark the 180th anniversary of Cezanne’s birth, in 2019 I published Cézanne: The Father of Modern Art (Takanori Nagaï, author and editor, Sangensha, 2019), in which I clarified how and when the widely held “Cezanne was the father of modern art” concept was formulated and how it was handed on. Consequently, as the continuation of that book, this book is an experiment at breaking free of that stereotyping, of heralding an entirely new image of Cezanne.

The following is a general overview of this book.

This book strips away the “father of modern art” label from Cezanne and relates him to the social environment of the day as it clarifies what value systems and motive forces led to his creative activities and what was the societal meaning of these factors. Cezanne did not set out to become the “father of modern art” gazing out upon the later generations of art that spread from his efforts after his death. Rather, this book heralds a new theory about how throughout his life Cezanne sought and established his own ways of creating, always from the premise that he positioned himself within his own time and society. He was aware of the major issues facing his times and place – whether the flood of ostentatious pictures engendered by the spread of commercialism, the permeation of indirect mechanical production with its loss of human scale in the face of advancing post industrial revolution mechanization, damage to the natural scenery by the flood of manmade items, or the loss of regional characteristics in the face of the France’s overall standardization as advances were made in the post French revolution centralization of authority – as he chose a truly human stance for the creation of his art, all while choosing his place in society as a critic of the modernization of his day.

Cezanne chose the search for “truth in painting” as his standpoint for responding to these social ills with creative activity. Asking the meaning of this search, and using it as the fulcrum of my examination, this book explains my theory which clarifies how the meaning of Cezanne’s practices were related to his artistic environment and his social environment.

The book’s structure and contents are presented in the following table-of-contents order. Section I outlines the book’s contents while Sections II through IV provide detailed discussions.

Section I. The Life and Works of a Painter who Sought “Truth in Painting”

This section clarifies my hypothesis that “truth in painting” was Cezanne’s lifelong mission,

from his earliest period through his final years, tracing the changes and vicissitudes in Cezanne’s life and oeuvre in chronological order, from early to mid and late periods. Here I also clarify the societal changes surrounding him and the artistic and philosophical environment of the artists, critics and others of his day, and analyze Cezanne’s artistic characteristics and major techniques.

Section II. Cezanne as Creative Subject

This section clarifies from the following three angles the answer to the question, what does “truth

in painting” mean as Cezanne’s creative fulcrum: Chapter 1, Cezanne’s View of Art as Seen in his Letters; Chapter 2, The Female Image as Arcadia; and Chapter 3, Refuting the ‘Fini’ Concept and Realization of Truth in Painting Concept.

In Chapter 1, I organized Cezanne’s extant comments found in his letters as I clarified his artistic view. I further clarified the phrase “réalisation des sensations” which is central to those views.

In Chapter 2, I traced the process whereby Cezanne formulated his own distinctive utopian art theory expressed in terms of the female image.

In Chapter 3, I clarified how Cezanne criticized the concept of fini, which painters in thrall to the Salon official exhibitions of the day gleefully followed, as nothing more than a false, contentless, deceit-filled put-on. In its place, he set as his unique artistic mission the expression of the world as he sensed it – a concept he summed up in the phrase “truth in painting” – and the ongoing pursuit/ invention of original techniques to realize this concept, such as the couillarde technique.

Section III. Cezanne’s Artistic Milieu

This section organizes Cezanne’s environment into four chapters, namely: Chapter 1, Artist; Chapter 2, Critic; Chapter 3, Collector; and Chapter 4, Craftsman and Designer. Cezanne established his own stance through his dialogue with great masters of the past whose works he copied at the Louvre, and resonance with the artistic views, creative activities and philosophies of his contemporaries. Formalist and psychoanalytical theories regarding Cezanne reduce Cézanne’s practices to entirely Cezanne’s own personal issues. This book interprets those practices as actions shared with his contemporaries, his collective network. There has been absolutely no such interpretation in the history of the study of Cezanne.

Chapter 1, Artist (Part 1) states that the real aim of Cezanne’s lifelong copying of artworks by the masters of the past in the Louvre and other collections was to establish his own methods through knowing the other, namely the masters of the past. Chapter 1, Artist (Part 2) questions what aspects of the Impressionist aesthetic Cezanne shared, what he rejected. In Chapter 1, Artist (Part 3) I borrow the eyes of two of his contemporaries, Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) and the Japanese poet,sculptor Kôtarô Takamura (1883-1956) to clarify the various artistic and philosophical questions that Cezanne shared with the sculptor Rodin.

Chapter 2, Critic (Part 4) analyzes the art theories of Cezanne’s friend the novelist Émile Zola and then Chapter 2, Critic (Part 5) clarifies the process by which he worked out his anti-Salon art theory (namely the search for “truth in painting”) as a joint process with Zola. This process of explaining that Cezanne established his art theory in conjunction with Zola’s art theory is a first in the history of Cezanne studies.

Chapter 3, Collector (Part 6) notes how the earliest collectors of Cezanne’s works were bohemians, independent and anti-establishment painters and thus those who resonated with Cezanne’s philosophical and societal standpoint. Further, I note that the first to realize the value of Cezanne’s autonomous paintings were the specially privileged class and they were absolutely not those collecting Cezanne works as asset building or speculation exercises. Rather, they collected because they discerned a place in society for themselves through participating in and supporting Cezanne’s aesthetic fight. Conversely, it was the presence of such collectors which allowed Cezanne to tread the path he had chosen. In this relationship we can see a type of joint work or joint process.

In Chapter 4, Craftsman and Designer (Part 7) I clarify that Cezanne resonated with Art Nouveau’s vitalism philosophy and contemporaneous nature. In Chapter 4, Craftsman and Designer (Part 8) I clarify the artistic problems that were being simultaneously confronted by Cezanne and the Art Nouveau decorative artists, and the philosophies they shared. In addition, Cezanne’s arts creatively and spiritually resonated with the designers of the beginning of the 20th century onward. This book is the first in the world to consider the contemporaneity between Cezanne and the decorative artists and designers of his day.

Section IV. Cezanne’s Places

This section classifies Cezanne’s “places” in two categories, terroir/land and society, and asks what kind of artistic stance choices were instigated by his allotted places, what kind of creative activities did he pursue.

Chapter 1, Terroir/Land of this section discusses the driving force role played by the terroir/ land in his creative work, the role of where he lived and worked. Each part of the chapter details these places – (Part 1) Paris, (Part 2) Provence, in southern France and (Part 3) Jas du Bouffan, the studio he built in Aix-en-Provence, and asks what were the stances selected by Cezanne, what were the creative and imaginative powers granted him by such positioning.

Chapter 1, Terroir/Land (Part 1) shows how the young Cezanne then living in Paris awakened to the potential for building a new art through a dialectic sublation of art (Paris) and nature (Provence) and further indicates how this attitude runs through his entire life as he traveled, back and forth, between Paris and Provence. Further, Cezanne was by no means a lofty painter, rather he built a broad human network in Paris, and here I clarify how Cezanne’s success in Paris was achieved via his interactions with avant-garde painters and the critics and collectors who supported them.

Chapter 1, Terroir/Land (Part 2) discusses how, unlike the modernizing urban metropolis of Paris, Cezanne spent his later years in Provence, a place not yet touched by modernization, and that setting led him to create a utopian world in his paintings. Like the “female image as utopia” discussed in Section II Chapter 2, this part shows how he had matured from his early period private utopia into an anti-modernist vision for society.

Chapter 1, Terroir/Land (Part 3) brings to light the original meaning of his works produced at his Jas du Bouffan studio over a forty-year period. In other words, the meaning that was lost amidst the movement of those works out of that studio and into the hands of collectors and museums.

Section IV Chapter 2, Society (Part 4) outlines the history of social history research and indicates the potential for Cezanne social history research. Section IV Chapter 2, Society (Part 5) discusses the meaning of the corporeal quality that appears in Cezanne’s drawings, and demonstrates how overall Cezanne’s artistic activities raised objections to a society in which everyday life is filled with manmade things born from indirect Post-Industrial Revolution mechanized production methods (regulated and standardized) and were themselves a constant effort to restore a sense of the human in the true meaning of the word.

In sum, this book thus concludes that Cezanne’s lifelong search for “truth in painting” was absolutely not a case of him being engrossed in his inner realm, but rather that his search was a type of societal participation, a practical social activity.

By recognizing the philsophical and social meaning of Cezanne’s artistic activities, in brief, his “search for truth in painting”, this book is an attempt to add a new link to the barely begun lineage of social history research on Cezanne.

It is my great hope that this book will provide an opportunity for Cezanne studies to set out in a new direction.

This book was published under the auspices of a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 2021 Grant-in-Aid for Publication of Scientific Research Results (Scientific books).

Prospectus en japonais :

Références

| ↑1 | Nina Maria Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence The Painter in His Culture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2003 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul Cézanne Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald Nouvelle édition réviée et augmentée, Bernard Grasset Éditeur, Paris, 1978, p. 315. |